The financial services landscape is undergoing a transformation as profound as any in its history. For generations, banking remained the exclusive domain of licensed financial institutions, their ornate buildings and complex regulations creating insurmountable barriers for anyone hoping to offer financial products. Yet today, ride-sharing apps provide instant payment accounts to drivers, e-commerce platforms offer business checking accounts to merchants, and software companies embed lending directly into their platforms. This revolution stems from Banking-as-a-Service, an infrastructure model that fundamentally changes who can offer banking products and how quickly they can reach market.

Traditional financial services operated within rigid boundaries where only chartered banks could hold deposits, process payments, or extend credit. Companies wanting to offer financial products faced a stark choice: spend years and millions of dollars obtaining banking licenses and building regulatory infrastructure, or abandon financial services entirely. This created a massive gap between consumer expectations shaped by digital experiences and the antiquated processes that dominated banking. Customers increasingly demanded seamless financial services integrated into their daily workflows, yet the technology and regulatory frameworks supporting traditional banking struggled to accommodate these expectations.

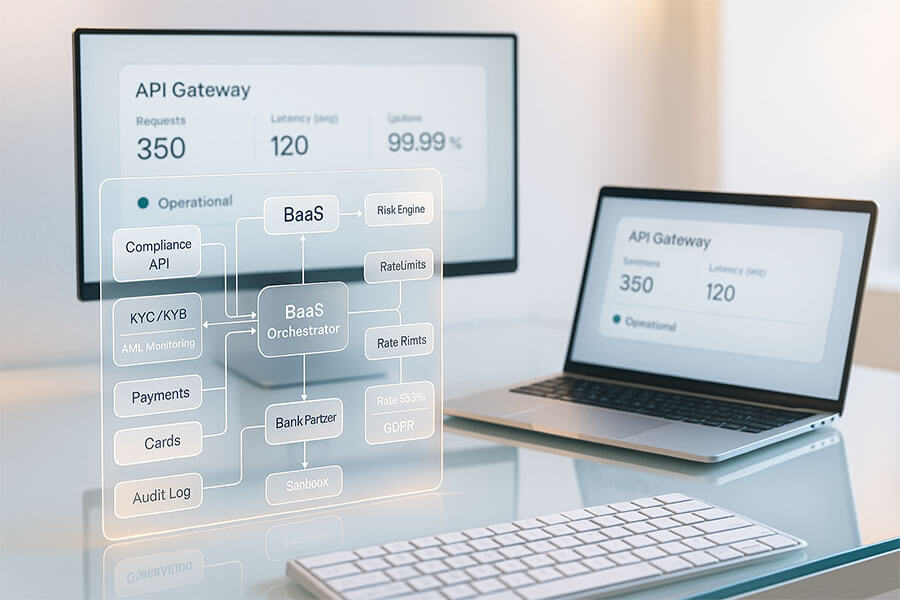

Banking-as-a-Service platforms emerged as the solution to this structural challenge. These platforms function as intermediaries between licensed banks and non-bank companies, providing the technological infrastructure, regulatory compliance frameworks, and operational capabilities that enable any business to offer banking services through application programming interfaces. Rather than building banking capabilities from scratch, companies can integrate pre-built financial services into their products through simple API calls, transforming months or years of development into weeks of implementation. The platform handles the complex regulatory requirements, manages relationships with sponsor banks, and provides the technical architecture needed to process millions of transactions securely and reliably.

The implications extend far beyond technical convenience. BaaS platforms democratize access to financial infrastructure, enabling smaller companies and innovative startups to compete with established financial institutions. They accelerate the pace of financial innovation by reducing the time and capital required to launch new products. Most importantly, they enable embedded finance, where financial services become invisible components of broader customer experiences rather than standalone products requiring separate accounts and interfaces. When a small business owner receives payments, manages cash flow, and accesses credit entirely within their accounting software, they experience the power of embedded finance enabled by BaaS architecture.

The market growth trajectory illustrates the profound impact BaaS is having on financial services. According to industry research, the global BaaS market was valued at approximately $716 billion in 2024 and is projected to reach $842 billion by 2025, reflecting a compound annual growth rate of 17.7%. This explosive growth stems from multiple converging trends including surging demand for digital banking solutions, the proliferation of smartphones enabling mobile-first financial experiences, increasing globalization requiring cross-border payment capabilities, and evolving regulatory frameworks that, despite their complexity, are gradually creating clearer pathways for non-traditional financial services providers. The adoption spans both large enterprises with substantial IT budgets seeking to integrate complex treasury and payment flows, and small to medium enterprises increasingly accessing banking infrastructure that was previously available only to major corporations.

This transformation arrives at a critical moment in financial services evolution. Consumers and businesses increasingly expect instant gratification, seamless digital experiences, and services tailored to their specific contexts. Traditional banks, constrained by legacy systems and conservative cultures, struggle to meet these expectations. Meanwhile, technology companies understand user experience and rapid iteration but lack banking licenses and regulatory expertise. BaaS platforms bridge this gap, combining the regulatory permissions of traditional banks with the innovation velocity of technology companies to create a new paradigm for financial services delivery.

Understanding BaaS platform architecture requires examining the intricate technical, regulatory, and operational components that enable non-banks to offer financial services safely and compliantly. The journey from traditional banking infrastructure to modern embedded finance represents not merely technological advancement but a fundamental reimagining of how financial services are created, delivered, and experienced in an increasingly digital economy.

Understanding Banking-as-a-Service Fundamentals

Banking-as-a-Service represents a fundamental restructuring of how financial services are delivered, transforming banking infrastructure from a proprietary asset controlled by individual institutions into a shared utility accessible through standardized interfaces. At its core, BaaS enables non-bank companies to offer banking products without obtaining banking licenses or building complex infrastructure. This model creates a three-sided ecosystem where licensed banks provide regulatory permissions and hold deposits, BaaS platforms provide technology and operational capabilities, and customer-facing companies integrate banking services through APIs.

The value proposition differs for each stakeholder but creates powerful alignment. Licensed banks, particularly smaller regional institutions, gain access to new customer segments and revenue streams without heavy investments in customer acquisition or digital development. BaaS platforms create scalable businesses by building infrastructure once and licensing it to multiple companies, generating recurring revenue from transaction fees and subscriptions. Customer-facing companies offer differentiated financial products that increase engagement and create new revenue streams without massive traditional investments.

This ecosystem operates through carefully structured relationships governed by detailed legal agreements, technical integrations, and operational procedures. The licensed bank maintains ultimate responsibility for regulatory compliance and customer funds. The BaaS platform provides APIs, compliance tools, and operational support. The embedded finance company maintains customer relationships and controls user experience while relying on partners for underlying banking operations.

Core Concepts and Ecosystem Stakeholders

The operational model requires precise coordination among multiple parties, each contributing specialized capabilities. Licensed banks in BaaS arrangements, called sponsor or partner banks, provide foundational infrastructure including deposit accounts, transaction processing, and most importantly, their banking charter and regulatory permissions. These banks undergo regular regulatory examination, maintain FDIC insurance, and bear ultimate legal responsibility for compliance including anti-money laundering, consumer protection, and capital adequacy standards.

BaaS platforms function as sophisticated middleware between sponsor banks and customer-facing companies, providing the technology stack, compliance frameworks, and operational capabilities needed for banking services at scale. These platforms typically offer modular services including account management, payment processing, card issuance, transaction monitoring, fraud detection, and regulatory reporting. Most platforms adopt microservices architectures enabling independent scaling and integration with diverse technology stacks.

Embedded finance companies range from e-commerce platforms and SaaS providers to ride-sharing apps and vertical market solutions. They integrate banking services to create comprehensive customer experiences, generate revenue, and increase retention. Common products include business checking accounts, payment processing, instant payouts, embedded lending, and corporate cards. Integration typically occurs through RESTful APIs that abstract underlying complexity.

The complexity necessitates sophisticated governance and risk management. Sponsor banks implement robust third-party risk management including due diligence, ongoing monitoring, regular audits, and escalation procedures. BaaS platforms invest heavily in compliance infrastructure including transaction monitoring, customer verification, and regulatory reporting. Economic incentives drive adoption despite complexity. Banks generate fee income with low marginal costs. BaaS platforms achieve high margins by amortizing development costs across customers. Embedded finance companies monetize customer bases through financial services offering better unit economics than core products.

BaaS Platform Architecture Components

The technical architecture of Banking-as-a-Service platforms represents sophisticated engineering handling unique financial services requirements while providing flexibility for diverse use cases. Unlike traditional banking systems built as monolithic applications, BaaS architectures prioritize external integration capabilities, real-time transaction processing, and modular services that customers can adopt independently. These platforms must achieve financial infrastructure reliability and security standards while maintaining cloud-native agility and scalability.

Modern BaaS platforms typically deploy on cloud infrastructure from Amazon Web Services, Microsoft Azure, or Google Cloud Platform, leveraging scalability, reliability, and security capabilities. Cloud deployment enables dynamic resource scaling, high availability through geographic redundancy, and rapid technology adoption. Architecture generally follows microservices design principles, decomposing banking functionality into independent services developed, deployed, and scaled separately. This enables concurrent development, facilitates testing without affecting the entire system, and allows granular scaling.

Database architecture balances transaction consistency, query performance, and regulatory compliance. Core financial data resides in relational databases providing strong consistency through ACID transactions, ensuring operations complete entirely or fail completely. Complementing transactional databases, platforms employ distributed caching for read performance, search engines for complex queries, and data warehouses for analytics and reporting.

Infrastructure and Technical Stack

The foundational infrastructure encompasses core systems for processing transactions, maintaining ledgers, and orchestrating complex workflows. The general ledger maintains authoritative records of all transactions and balances with banking regulation precision. Modern ledger implementations use append-only designs where transactions are recorded as immutable events, providing complete audit trails and enabling point-in-time account reconstruction. These ledgers must process high volumes with low latency while maintaining strict consistency.

Payment processing engines handle complex choreography for moving money between accounts, involving transaction validation, balance checking, account debiting and crediting, state management, and external network coordination. These engines implement sophisticated state machines tracking transactions through their lifecycle, handling failures gracefully and ensuring incomplete transactions can be recovered or reversed. Integration with external networks including ACH, wire transfers, card networks, and real-time payment systems requires adapters translating between internal formats and external protocols.

The technical challenges of building reliable payment processing extend to handling various edge cases and error conditions that can occur throughout transaction lifecycles. Network timeouts during external system communication require careful timeout management and retry logic to ensure transactions either complete successfully or fail cleanly without duplicate processing. Idempotency mechanisms allow clients to safely retry failed requests without risk of processing the same transaction multiple times, typically implemented through unique transaction identifiers that the platform checks before processing. Reconciliation processes continuously compare internal transaction records with external system confirmations to identify and resolve discrepancies, ensuring that all parties agree on transaction outcomes and account balances. These reconciliation procedures become particularly critical when dealing with delayed settlement systems like ACH, where transactions may take days to fully complete and can be reversed or returned due to insufficient funds or account problems discovered after initial acceptance.

Security infrastructure implements defense-in-depth strategies with multiple protection layers. Encryption protects data at rest and in transit, with sensitive information encrypted at the application layer using keys managed through dedicated services. Network security implements virtual private clouds, web application firewalls, and distributed denial-of-service protection. Authentication systems verify request identity and permissions, implementing multi-factor authentication, role-based access controls, and comprehensive audit logging.

Monitoring systems provide visibility for reliable operations, collecting performance metrics, tracing requests through microservices, aggregating logs, and generating alerts. These systems track business metrics including transaction volumes and success rates alongside infrastructure metrics. Real-time dashboards enable operations teams to understand system health while historical data enables capacity planning. The observability infrastructure also supports root cause analysis when problems occur, allowing engineers to trace individual transactions through complex distributed systems to identify exactly where failures happened and what conditions triggered them. This capability proves essential for maintaining the high reliability standards financial services demand, as even small percentages of failed transactions can represent significant numbers of frustrated customers and potential regulatory issues when transaction volumes reach millions per day.

API Layer and Integration Framework

The API layer represents the primary interaction point between BaaS platforms and customers, transforming complex banking operations into simple HTTP requests developers can integrate with minimal specialized knowledge. REST APIs dominate due to simplicity, widespread adoption, and alignment with modern web development. These APIs expose banking functionality through resource-oriented endpoints where accounts, transactions, and cards are modeled as resources created, retrieved, updated, or deleted through standard HTTP methods.

API design emphasizes developer experience, recognizing that integration ease directly impacts adoption and time-to-market. Comprehensive documentation provides technical references, conceptual guides, tutorials, and code examples. Interactive API explorers allow endpoint testing without code. Software development kits in popular languages provide idiomatic wrappers around HTTP requests, handling authentication, errors, and serialization.

Authentication typically implements OAuth 2.0 or API key-based schemes providing secure access delegation. API keys enable usage tracking, rate limiting, and access revocation, while OAuth enables fine-grained permissions. Webhook systems push notifications to customer applications when significant events occur, enabling real-time responses without constant polling. Webhooks deliver JSON payloads with signatures for verification and implement retry logic for delivery failures.

Version management balances innovation with stability for existing integrations. Most platforms maintain multiple API versions concurrently, allowing customers to adopt new versions on their schedules. Version identifiers appear in URLs, headers, or content types. Deprecation policies provide advance notice before removing old versions. Rate limiting protects platforms from overload while ensuring fair resource allocation, tracking request volumes per customer and endpoint with configurable limits varying by subscription level.

Compliance, Licensing, and Regulatory Framework

The regulatory landscape surrounding Banking-as-a-Service represents perhaps the most complex aspect of the model, involving regulations designed for traditional banks applied to distributed ecosystems where responsibilities are shared among multiple parties. Banking regulations in the United States operate through a dual system where institutions receive charters from federal or state authorities, each bringing different requirements, examination processes, and supervisory approaches. Federal regulators including the Federal Reserve, Office of the Comptroller of the Currency, and FDIC establish rules governing capital adequacy, risk management, consumer protection, and operational soundness.

The fundamental principle is that chartered banks bear ultimate responsibility for all activities under their license, including third-party services. Sponsor banks in BaaS arrangements cannot simply outsource operations while absolving themselves of regulatory obligations. They must implement comprehensive third-party risk management including extensive due diligence, ongoing monitoring, regular audits, and documented contingency plans. Regulators have emphasized these expectations through enforcement actions against banks whose BaaS programs exhibited control weaknesses.

Consumer protection regulations impose detailed requirements on how financial products are marketed, disclosed, and operated. The Truth in Savings Act requires clear disclosure of rates, fees, and terms. The Electronic Fund Transfer Act protects consumers using electronic payments, establishing error resolution and unauthorized transaction liability rules. The Equal Credit Opportunity Act prohibits lending discrimination. These regulations apply regardless of whether services are provided through bank branches or embedded platforms, requiring robust compliance processes.

The Bank Secrecy Act and its implementing regulations create extensive anti-money laundering obligations that BaaS ecosystems must carefully navigate. Financial institutions must implement customer identification programs that verify the identity of account holders using government-issued documents and cross-reference information against sanctions lists and databases of known criminals. Ongoing transaction monitoring must identify suspicious patterns that might indicate money laundering, terrorist financing, fraud, or other illicit activities, with detected issues reported to the Financial Crimes Enforcement Network through Suspicious Activity Reports. These requirements extend through the entire BaaS ecosystem, with sponsor banks bearing ultimate responsibility but typically requiring BaaS platforms and embedded finance companies to implement front-line controls and monitoring systems. The complexity increases when dealing with business accounts, as beneficial ownership rules require identifying and verifying the actual individuals who own or control legal entities opening accounts, preventing criminals from hiding behind shell companies or complex ownership structures.

Licensing Models and Requirements

Banking-as-a-Service operations can be structured through several licensing models, each involving different legal relationships, risk allocations, and operational requirements. The sponsor bank model, most common, involves a licensed bank partnering with a BaaS platform and allowing embedded finance companies to offer services under the bank’s license. The bank maintains customer accounts, holds deposits, and processes transactions, while the BaaS platform provides technology and the embedded finance company manages customer relationships. The bank receives fees and assumes regulatory responsibility, typically requiring indemnification from partners.

State money transmitter licenses provide an alternative for payment-focused companies. These state-issued licenses allow receiving and transmitting money without bank charters. Companies must obtain licenses in each operating state, meet varying bonding requirements, implement anti-money laundering programs, and submit regular reports. This offers more direct control than sponsor arrangements but requires navigating state-by-state requirements with higher maintenance costs.

Some larger companies pursue banking charter acquisition, providing maximum control but requiring substantial commitments. Obtaining a de novo charter typically requires minimum capital of tens of millions, assembling experienced management teams, developing comprehensive plans, and enduring multi-year application processes. Once chartered, institutions face ongoing examination, capital requirements, and full banking regulations.

The choice among models involves trade-offs between speed-to-market, capital requirements, operational control, and regulatory complexity. Sponsor arrangements enable fastest entry with minimal capital but provide least autonomy. Money transmitter licenses offer more control while avoiding bank regulation but require significant compliance investments. Banking charters provide maximum autonomy but demand substantial capital and permanent regulatory oversight. The regulatory environment evolved significantly in 2024 as enforcement actions revealed supervisory concerns about inadequate oversight, weak compliance controls, and third-party risk management failures, prompting enhanced scrutiny and consolidation around better-capitalized institutions.

Security and Operations Management

Operating a Banking-as-a-Service platform requires maintaining security and operational standards exceeding typical technology companies while providing reliability expected of critical financial infrastructure. These platforms process millions in daily transactions, store sensitive personal and financial information, and serve as key business components, meaning any outage or breach can have severe consequences. This demands investment in sophisticated security architectures, operational processes, and monitoring systems that anticipate and mitigate diverse threats and failure modes.

Security threats span traditional cybersecurity concerns including network intrusions, malware, and denial-of-service attacks as well as financial fraud exploiting weaknesses in identity verification, transaction monitoring, or authentication. Platforms must defend against external attackers attempting data or fund theft while preventing internal threats from employees with legitimate access. Social engineering attacks manipulating representatives or customers represent persistent threats requiring security awareness training alongside technical controls.

Operational resilience extends beyond security to encompass processes and systems maintaining service availability, reliable transaction processing, and failure recovery. Financial services demand extremely high availability, typically targeting four nines reliability or better. Achieving this requires redundant systems across multiple data centers, automated failover detecting failures and redirecting traffic, and careful capacity planning. Regular disaster recovery exercises verify backup systems work correctly.

Security Architecture and Risk Controls

Security architecture implements multiple defensive layers protecting against diverse threats while maintaining usability and performance. Network security isolates sensitive systems from public internet access through proxy layers filtering malicious requests and implementing rate limiting. Web application firewalls analyze HTTP traffic for attack patterns including SQL injection and cross-site scripting. Distributed denial-of-service protection absorbs attack traffic through globally distributed scrubbing centers.

Application security encompasses how code handles data, validates inputs, and implements business logic. Secure development practices including threat modeling, code review, and automated security scanning help identify vulnerabilities before production. Input validation rigorously checks data from users or external systems. Output encoding ensures user-supplied data displayed in web pages cannot execute as code. Parameterized database queries prevent SQL injection.

Identity and access management controls who can access systems and what actions they can perform, implementing least privilege where users and services receive only minimum necessary permissions. Multi-factor authentication requires multiple evidence forms before granting sensitive system access. Role-based access control defines permissions based on job functions. Privileged access management addresses administrative account risks through additional controls including approval workflows and time-limited access.

Fraud prevention systems analyze transaction patterns identifying potentially fraudulent activity before causing losses. Machine learning models trained on historical fraud data predict transaction fraud likelihood based on factors including size, recipient, velocity, and device characteristics. High-risk transactions may be blocked automatically, subjected to additional verification, or flagged for manual review. These systems continuously adapt as fraud patterns evolve.

Compliance monitoring tracks transaction activity identifying potential money laundering, terrorist financing, or illicit activities. These systems implement sophisticated rules flagging suspicious patterns such as structuring or unusual activity inconsistent with customer patterns. Transaction monitoring reviews billions of transactions to identify the small fraction requiring investigation. Case management workflows enable compliance analysts to investigate flagged activity and determine whether suspicious activity reports should be filed with regulators.

Embedded Finance Applications and Case Studies

The practical application of Banking-as-a-Service infrastructure has spawned diverse embedded finance implementations across industries, demonstrating how financial services integrated into domain-specific platforms create value for users and competitive advantages for companies. These implementations range from simple payment facilitation to comprehensive banking services. Understanding real-world applications reveals both the tremendous potential and the practical challenges companies face transitioning from concept to operational reality.

E-commerce platforms have emerged as natural early adopters, as their core businesses already involve payment processing and their customers frequently need business banking, working capital financing, and payment facilitation. By embedding these services directly into platforms, e-commerce companies create seamless experiences where merchants manage entire businesses through single interfaces. This integration drives higher merchant engagement and generates significant financial services revenue often exceeding core e-commerce functionality economics.

Software-as-a-service companies serving vertical markets have discovered that embedding industry-specific financial services creates powerful value propositions justifying premium pricing and reducing churn. Construction management software enabling progress billing and lien management provides more value than generic project management tools. Property management platforms offering rent collection and maintenance vendor payments become indispensable to landlords. Healthcare practice management incorporating patient payment plans solves pain points generic scheduling software cannot address.

Real-World Implementations

Shopify’s implementation through Shopify Balance demonstrates how e-commerce platforms can leverage BaaS infrastructure to provide comprehensive financial services. Launched in 2023, Shopify Balance partnered with Stripe Treasury for BaaS capabilities and Evolve Bank & Trust as sponsor bank, enabling business checking accounts directly within merchant administration interfaces. The product provides merchants with faster access to Shopify Payments proceeds, typically receiving funds within one business day compared to two-to-five-day standards for traditional transfers. Account balances earn annual percentage yield rewards of 3.39% for standard merchants and 4.43% for Shopify Plus subscribers, rates significantly higher than typical business checking accounts.

Strategic value extends beyond direct financial services revenue to include increased merchant stickiness and platform engagement. Merchants using Shopify Balance consolidate more business operations onto the Shopify platform rather than managing finances through separate banking relationships, creating switching costs that reduce churn. The company expanded the offering in 2024 with Shopify Credit, a pay-in-full Visa business card offering up to 3% cashback on eligible purchases with flexible payment terms. These products address cash flow challenges small e-commerce businesses frequently face, providing working capital through credit while accelerating access to sales proceeds.

Uber’s evolution of financial services for drivers illustrates how embedded finance can address unique gig economy worker needs while creating competitive advantages in talent acquisition. The company initially launched Uber Money in 2019, partnering with Green Dot Bank to provide debit accounts enabling instant access to trip earnings rather than requiring drivers to wait for scheduled payouts. This addressed a critical pain point for drivers depending on immediate earnings access for daily expenses, while providing Uber with driver recruitment differentiation during driver shortages. The program evolved in 2022 when Uber launched the Uber Pro Card in partnership with Marqeta for card issuance and Branch for banking services, offering drivers up to 7% cashback on gas purchases when they achieve Diamond status.

The embedded banking services provided tangible value through features including automatic trip earnings deposits, fee-free transfers to external accounts, cashback rewards on common expenses, and budgeting tools within the driver app. For Uber, the program created multiple benefits including reduced driver churn as financial services increased stickiness, competitive recruitment advantage, and incremental revenue from interchange fees. The company reported in 2024 that drivers using the Uber Pro Card drove 12% more trips on average than those without it, demonstrating how financial services integration can influence user behavior beyond direct financial metrics.

The collapse of Synapse in 2024 provides a sobering counterpoint to success stories, revealing systemic risks when BaaS arrangements lack adequate oversight. Synapse, which supported approximately 100 fintech companies serving 10 million end users, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in April 2024 after its largest customer Mercury migrated to direct bank relationships. The bankruptcy exposed critical failures in transaction reconciliation and fund tracking, ultimately freezing an estimated $265 million in customer deposits across multiple partner banks including Evolve Bank & Trust. Customers of Synapse-powered fintechs including Yotta, Juno, and Copper lost access to funds for months, with some still unable to recover deposits as of early 2025.

The crisis revealed fundamental weaknesses in BaaS arrangement structuring and oversight, particularly regarding recordkeeping and fund reconciliation. Synapse maintained pooled For Benefit Of accounts at multiple partner banks, with Synapse’s internal ledgers serving as the only record of customer balances. When Synapse shut down operations, neither banks nor fintechs could determine customer balances with certainty. Subsequent investigations revealed discrepancies of tens of millions between Synapse’s ledgers and what banks actually held. The FDIC proposed new recordkeeping requirements in October 2024 requiring sponsor banks to maintain detailed ledgers of customer funds in custodial accounts, explicitly designed to prevent future Synapse-style failures.

The human impact of the Synapse collapse extended far beyond financial losses to disrupt the lives of tens of thousands of individuals who relied on these accounts for daily living expenses. Yotta customers, numbering approximately 85,000 with a combined $112 million in frozen savings, found themselves unable to pay rent, purchase groceries, or cover medical expenses. Some individuals borrowed money from family and friends for basic necessities, while others postponed surgeries, weddings, and other significant life events indefinitely due to lack of access to their own funds. The crisis highlighted a critical gap in consumer protections for fintech users, as FDIC insurance that should have protected these deposits proved ineffective when the fundamental problem was not bank failure but rather inability to determine which customers owned which funds due to inadequate recordkeeping. Federal regulators ultimately intervened with proposals to strengthen oversight and require better fund tracking, but for affected customers these regulatory improvements came too late to prevent months of financial hardship and ongoing uncertainty about whether they would ever fully recover their deposits.

The Synapse collapse triggered significant regulatory scrutiny of BaaS arrangements, with enforcement actions against several sponsor banks in 2024 citing inadequate third-party risk management and oversight. Banks were ordered to improve due diligence, implement enhanced partner monitoring, and establish clearer documentation of responsibilities and data flows. The crisis accelerated BaaS sector consolidation as smaller, less well-capitalized platforms struggled to meet enhanced regulatory expectations while larger players with more robust compliance infrastructure gained market share.

Benefits and Challenges

The Banking-as-a-Service model presents compelling advantages for multiple stakeholders while introducing complex challenges requiring careful management. For embedded finance companies, the primary benefit lies in dramatically reduced time-to-market for financial products compared to traditional approaches requiring banking licenses and custom infrastructure. Companies can launch banking features in weeks or months rather than years, enabling rapid experimentation and iteration. This speed advantage proves particularly valuable in competitive markets where being first to offer innovative financial services can establish sustainable positions. Lower upfront capital requirements make financial services accessible to smaller companies and startups that could never pursue traditional banking models.

Economic benefits extend beyond reduced development costs to include highly attractive unit economics often exceeding core product profitability. Financial services typically generate recurring revenue through transaction fees, interchange income from card programs, interest income on deposits, and subscription fees for premium features. These revenue streams often demonstrate favorable marginal economics as they scale. Companies report that customers using embedded financial products typically demonstrate higher engagement, longer retention, and greater lifetime value than those using only core features.

For licensed banks participating as sponsors, the model provides access to customer segments and transaction volumes they could not reach through traditional channels. Regional and community banks particularly benefit by leveraging their banking licenses as strategic assets without requiring massive technology, marketing, or branch investments. Fee income from BaaS relationships can be substantial with relatively low marginal costs. Banks also gain valuable insights into emerging fintech business models potentially informing their own digital transformation. The strategic importance of BaaS for smaller financial institutions has grown as traditional relationship banking faces challenges from larger competitors offering superior digital experiences and nationwide reach, making BaaS partnerships an increasingly attractive alternative to expensive internal technology development or competitive disadvantage.

End customers benefit most directly through improved financial services access, better user experiences, and features tailored to specific needs. Small business owners receive banking services integrated into platforms they already use, eliminating separate banking relationships. Gig economy workers gain instant earnings access and financial tools designed for irregular income. Consumers accessing embedded lending receive credit offers at point of need with streamlined applications. These improvements in convenience, speed, and contextual relevance represent genuine innovations benefiting users regardless of underlying technology.

The challenges facing BaaS adoption span technical, regulatory, and operational dimensions. Technical complexity represents a significant barrier as integrating financial services requires careful attention to security, transaction consistency, regulatory compliance, and error handling exceeding typical software development. Companies accustomed to rapid iteration find financial services demand much higher reliability standards, as transaction errors can have serious financial consequences and regulatory implications. Edge case handling including failed transactions, duplicate requests, and race conditions adds substantial complexity.

Regulatory risk creates ongoing uncertainty for BaaS participants as the framework governing these models continues evolving. Embedded finance companies must navigate complex compliance obligations despite lacking banking expertise, while sponsor banks face heightened third-party risk management scrutiny. The Synapse collapse demonstrated that regulatory failures can result in catastrophic outcomes including frozen funds and potential permanent losses, triggering enhanced oversight increasing compliance costs and prompting some banks to exit BaaS programs.

Operational challenges emerge from inherent coordination complexity among multiple parties with different incentives, capabilities, and risk tolerances. Communication breakdowns can result in compliance failures, service disruptions, or customer service problems where no party has complete visibility or authority to resolve issues. Division of responsibilities for customer support, fraud investigation, and regulatory reporting can create confusion. When disputes arise among partners about fees, liability, or performance expectations, resolution can be difficult.

Vendor dependence represents a strategic risk as companies become reliant on platform capabilities, stability, and business continuity. If a BaaS platform experiences financial difficulties, shuts down, or gets acquired with resulting strategy changes, customers may face significant disruption. The Synapse bankruptcy vividly illustrated these risks. While contracts typically include protections and transition assistance obligations, practical challenges of switching providers while maintaining service continuity can be substantial. Customer experience challenges associated with distributed responsibility can undermine the seamlessness embedded finance promises. When customers encounter problems, they may not understand whether to contact the embedded finance company, the BaaS platform, or the sponsor bank. Support representatives may lack access to information or tools needed for quick resolution, requiring escalation with resulting delays.

Final Thoughts

Banking-as-a-Service represents far more than incremental improvement in financial services delivery—it embodies a fundamental democratization of financial infrastructure that promises to reshape who can offer banking products and how innovation occurs in one of the economy’s most essential sectors. The transformation unleashed by BaaS platforms extends beyond technical architecture or business models to strike at the core question of financial inclusion, asking whether access to sophisticated banking capabilities should remain the exclusive province of large institutions or become widely available utilities that any company can leverage to serve its customers better.

The broader societal implications of this shift merit serious consideration as we evaluate the true impact of Banking-as-a-Service beyond commercial success metrics. Financial services have historically concentrated in major urban centers, large corporations, and affluent customer segments where scale economics justify infrastructure investments and regulatory compliance costs. This concentration has left underserved populations including small businesses, gig economy workers, rural communities, and lower-income individuals with limited access to banking services or forced to rely on predatory alternatives like check cashing services and payday lenders. BaaS platforms enable technology companies to embed banking services into products serving these underserved segments, potentially extending financial inclusion to populations that traditional banks have struggled or chosen not to reach profitably.

The intersection of technology and social responsibility becomes especially salient when examining how embedded finance can address persistent inequities in financial access. Small businesses in developing economies or rural areas can access business banking through e-commerce platforms without requiring local bank branches. Gig workers receive instant payment capabilities and financial management tools designed for irregular income streams that traditional banks often view as too risky or complicated. Immigrants can send remittances through platforms serving their communities with transparent pricing and convenient interfaces that compete with exploitative traditional money transfer services. These applications demonstrate how technology companies, when equipped with banking infrastructure through BaaS platforms, can innovate in market segments where incumbents lack incentives or capabilities to serve effectively.

Looking toward the future, Banking-as-a-Service seems poised to accelerate the ongoing disaggregation of financial services, where monolithic banks offering comprehensive products give way to specialized providers offering best-in-class capabilities in specific domains. This specialization mirrors transformations that have occurred in other industries where vertically integrated incumbents were disrupted by modular ecosystems enabling best-of-breed solutions. The implications for competition, innovation, and customer choice appear largely positive as increased specialization drives quality improvements and reduces switching costs by making it easier to adopt better solutions without abandoning entire banking relationships.

The ongoing regulatory challenges facing BaaS arrangements represent not obstacles to overcome but rather necessary guardrails ensuring that innovation serves customers responsibly while maintaining financial system stability. The Synapse collapse revealed genuine weaknesses in oversight and recordkeeping that could have been prevented through clearer regulatory expectations and more rigorous compliance. The enhanced scrutiny that followed, while creating near-term friction, should ultimately strengthen the industry by establishing clearer standards, eliminating inadequately capitalized participants, and providing greater certainty about regulatory expectations. This evolution parallels other technology-driven financial innovations that initially operated in regulatory gray areas before maturing into well-regulated industries that balance innovation with appropriate consumer protections.

The responsibility for ensuring BaaS fulfills its transformative potential while avoiding systemic risks extends to all ecosystem participants. Licensed banks must implement robust third-party risk management that goes beyond checking compliance boxes to genuinely understanding and monitoring their partners’ operations. BaaS platforms must invest continuously in compliance infrastructure, operational resilience, and security capabilities that match the critical role they play in the financial system. Embedded finance companies must approach financial services with the seriousness they demand, implementing appropriate controls and expertise rather than treating banking capabilities as just another API to integrate. Regulators must provide clear expectations while remaining flexible enough to accommodate innovation and experimentation that serves customers well.

The ultimate measure of Banking-as-a-Service success will not be the number of platforms launched or the transaction volumes processed but rather whether this model genuinely expands financial access and improves experiences for underserved populations who have too long been excluded from the benefits of modern banking. The technical achievements of building scalable API infrastructure and the business successes of companies monetizing embedded finance matter primarily as enablers of this broader social impact. When a small business owner in a rural community accesses working capital through their point-of-sale system, when an immigrant sends money home at fair rates through an app serving their community, when a gig worker manages irregular income through tools designed for their reality rather than traditional employment patterns, Banking-as-a-Service achieves its highest purpose.

The transformation underway in financial services infrastructure promises to continue accelerating as more companies discover the competitive advantages and revenue opportunities embedded finance offers. This evolution will undoubtedly produce both successes worthy of celebration and failures requiring correction, as all significant innovations do. The path forward requires balancing enthusiasm for innovation’s potential with appropriate caution about its risks, maintaining focus on serving customers well while building sustainable businesses, and ensuring that democratization of financial infrastructure produces genuine financial inclusion rather than merely new ways for technology companies to extract value from vulnerable populations. The stakes are high, the challenges are real, but the potential rewards for society justify continued investment in making Banking-as-a-Service work for everyone.

FAQs

- What is Banking-as-a-Service and how does it differ from traditional banking?

Banking-as-a-Service is an infrastructure model where licensed banks partner with technology platforms to enable non-bank companies to offer banking products through APIs. Unlike traditional banking where customers interact directly with chartered financial institutions, BaaS allows companies to embed financial services into their products while sponsor banks provide regulatory licenses and hold customer funds. This enables faster innovation and more contextual financial services integrated into industry-specific platforms, though it involves more complex multi-party relationships compared to traditional direct banking relationships. - Who are the main participants in a BaaS ecosystem?

The BaaS ecosystem involves three primary stakeholders working together to deliver financial services. Licensed banks, often called sponsor banks, provide banking charters, hold deposits, and bear ultimate regulatory responsibility. BaaS platforms provide the technology infrastructure, APIs, and operational capabilities that connect banks with embedded finance companies. Embedded finance companies integrate banking services into their products and maintain direct customer relationships. These parties coordinate through detailed legal agreements and technical integrations, with each contributing specialized capabilities essential to delivering seamless financial services. - What are the main security concerns with BaaS platforms?

BaaS platforms face security threats including external cyberattacks attempting to steal funds or data, internal threats from employees or contractors with system access, and fraud schemes exploiting weaknesses in identity verification or transaction monitoring. Platforms implement multiple defensive layers including encryption, network isolation, application security controls, and fraud detection systems. However, the distributed nature of BaaS arrangements where responsibilities span multiple parties can create security gaps if coordination and visibility are inadequate. The Synapse collapse demonstrated that operational and reconciliation failures can prove as devastating as traditional security breaches. - How much does it cost to implement BaaS services?

BaaS implementation costs vary significantly based on the scope of services, transaction volumes, and chosen platform. Most BaaS platforms charge combinations of setup fees ranging from tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands of dollars, monthly platform fees, and per-transaction fees on activities like account creation, payments, or card issuance. Sponsor banks also receive fees for regulatory and banking services. Total costs for moderate transaction volumes might range from several thousand to tens of thousands of dollars monthly, though high-volume implementations can cost substantially more. Companies should budget for ongoing compliance, integration, and operational costs beyond platform fees. - What regulatory compliance requirements apply to BaaS arrangements?

BaaS arrangements must comply with the full spectrum of banking regulations including consumer protection laws like the Truth in Savings Act and Electronic Fund Transfer Act, anti-money laundering and know-your-customer requirements under the Bank Secrecy Act, fair lending laws prohibiting discrimination, and operational regulations governing capital adequacy and risk management. Sponsor banks bear ultimate regulatory responsibility and face increasing scrutiny of their third-party risk management practices. Embedded finance companies must implement compliance processes even though they lack banking licenses, while BaaS platforms typically provide compliance infrastructure and tools that partners use to meet obligations. - Can small companies compete with large enterprises using BaaS platforms?

BaaS platforms democratize access to banking infrastructure that was previously available only to large institutions, enabling small companies to offer sophisticated financial services comparable to those provided by major competitors. The modular nature of BaaS allows companies to start with basic services and expand capabilities as they grow, avoiding large upfront investments. However, small companies face challenges including higher per-transaction costs due to lower volumes, limited negotiating leverage with platforms and banks, and resource constraints for implementing proper compliance and security controls. Success requires choosing appropriate partners, focusing on differentiated offerings rather than competing on price or scale, and building compliance expertise internally or through specialized consultants. - What happens to customer funds if a BaaS platform fails?

Customer funds in properly structured BaaS arrangements should be held in FDIC-insured accounts at licensed banks, providing protection up to standard insurance limits even if the BaaS platform or embedded finance company fails. However, the Synapse collapse revealed that inadequate recordkeeping can freeze funds even when they technically remain at insured banks, if parties cannot determine which funds belong to which customers. The FDIC has proposed new recordkeeping requirements specifically designed to prevent this scenario by requiring sponsor banks to maintain independent records of customer balances. Companies evaluating BaaS providers should verify fund holding arrangements, understand contingency procedures for provider failures, and potentially maintain relationships with multiple providers to mitigate concentration risk. - How do BaaS platforms integrate with existing business systems?

BaaS platforms provide RESTful APIs that companies integrate into their applications using standard web development techniques. Most platforms offer software development kits in popular programming languages that simplify integration by handling authentication, error handling, and request formatting. Integration typically requires connecting the BaaS API to the company’s user database for account creation, integrating payment APIs into checkout or billing flows, implementing webhook handlers to receive real-time notifications of events, and building user interfaces for banking features. The complexity varies from simple implementations requiring weeks of development to complex integrations spanning months. Platforms provide documentation, code examples, and technical support to facilitate integration, though companies need engineering resources with API integration experience and willingness to learn financial services domain concepts. - What are some successful examples of BaaS implementation?

Shopify Balance launched in 2023 using Stripe Treasury and Evolve Bank & Trust to provide business checking accounts integrated into the Shopify merchant admin, offering faster payouts and competitive interest rates that increased merchant engagement. Uber implemented financial services for drivers through partnerships with Green Dot and later Marqeta and Branch, providing instant earnings access and cashback rewards that improved driver retention. These examples demonstrate how companies can leverage BaaS infrastructure to create differentiated financial products serving their specific customer bases. However, the Synapse collapse in 2024 serves as a cautionary example of risks when BaaS arrangements lack adequate oversight, proper recordkeeping, and sufficient capitalization. - What skills and resources are needed to successfully implement BaaS?

Successful BaaS implementation requires engineering capabilities to integrate APIs and build user interfaces, compliance expertise to navigate banking regulations and implement required controls, product management skills to design financial services that serve customer needs while remaining compliant, and operational capabilities to handle customer support, fraud management, and regulatory reporting. Small companies often lack these capabilities internally and must partner with consultants, hire specialized talent, or rely heavily on BaaS platform support. The learning curve can be steep for companies without financial services experience, as banking involves unique considerations around transaction consistency, regulatory compliance, and security that differ from typical software development. Companies should plan for substantial investment in education and potentially phased implementation that starts with simpler services before expanding to more complex offerings.