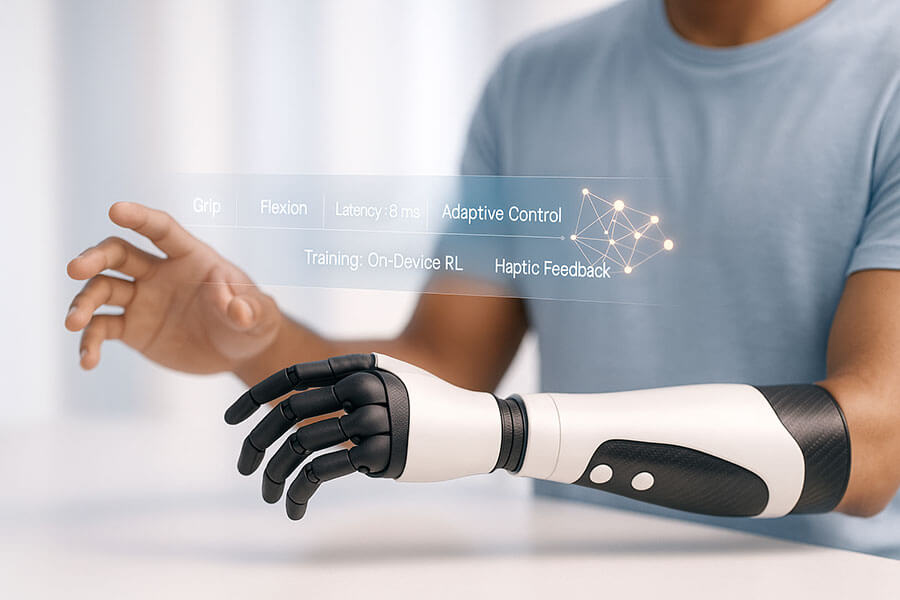

The intersection of artificial intelligence and prosthetic technology represents one of the most promising frontiers in modern healthcare, where sophisticated algorithms are fundamentally transforming how artificial limbs understand and respond to human intent. Reinforcement learning, a branch of machine learning that enables systems to learn through trial and error, has emerged as a revolutionary approach to prosthetic control, offering unprecedented levels of adaptability and personalization that were unimaginable just a decade ago. Unlike traditional prosthetic systems that rely on pre-programmed movements and fixed control schemes, reinforcement learning algorithms continuously evolve and improve their performance by learning from each interaction with their users, creating a dynamic partnership between human and machine that grows stronger over time.

For the millions of people worldwide living with limb loss, the promise of reinforcement learning extends far beyond simple mechanical replacement of missing body parts. These intelligent systems represent a fundamental shift in how prosthetics integrate with the human body and mind, learning to interpret subtle variations in muscle signals, adapting to changing environments, and even anticipating user intentions based on patterns observed over time. The technology works by establishing a reward system where successful movements and accurate interpretations of user intent are reinforced, while errors lead to algorithmic adjustments that improve future performance. This continuous learning process means that each prosthetic limb becomes uniquely attuned to its user, developing an increasingly natural and intuitive control interface that can restore not just function, but confidence and independence.

The transformative potential of reinforcement learning in prosthetics extends across multiple dimensions of daily life, from enabling precise manipulation of delicate objects to facilitating complex athletic movements that require split-second coordination. As these systems accumulate experience through thousands of daily interactions, they build sophisticated models of user behavior that allow them to distinguish between intentional commands and involuntary muscle movements, adapt to fatigue or changes in muscle strength, and even compensate for environmental factors like carrying heavy loads or walking on uneven terrain. This adaptive intelligence represents a paradigm shift from viewing prosthetics as static tools to understanding them as evolving partners in the rehabilitation journey, capable of learning and growing alongside their users to provide increasingly seamless integration with the human body.

Understanding Reinforcement Learning in Healthcare Context

Reinforcement learning stands apart from other forms of artificial intelligence through its unique approach to problem-solving, which mirrors the fundamental ways humans and animals learn from experience in the natural world. In the healthcare context, this learning paradigm offers particular advantages because it can handle the complexity and variability inherent in biological systems, adapting to individual differences in anatomy, physiology, and behavior patterns that would overwhelm traditional programming approaches. The core principle involves an agent, in this case the prosthetic control system, that learns to make decisions by receiving feedback from its environment through a carefully designed system of rewards and penalties that guide it toward optimal performance over time.

The mathematical foundations of reinforcement learning rest on the concept of maximizing cumulative reward, where the algorithm learns to associate certain actions with positive outcomes and others with negative consequences, gradually building a policy that guides future behavior. In prosthetic applications, this translates to the system learning which motor commands produce smooth, accurate movements that match user intent, and which lead to jerky, imprecise, or unintended actions that frustrate the user or fail to accomplish the desired task. Through thousands of iterations, the algorithm develops an increasingly sophisticated understanding of the relationship between sensor inputs, control signals, and movement outcomes, creating a personalized control strategy that becomes more refined with each use.

The Basics of Machine Learning and AI

Machine learning represents a fundamental departure from traditional computer programming, where instead of explicitly coding every possible scenario and response, systems are given the ability to learn patterns from data and make decisions based on that learned experience. Think of it as teaching a computer in much the same way you might teach a child to ride a bicycle, not by providing detailed instructions for every possible situation, but by allowing them to practice, make mistakes, and gradually improve through experience. In the context of prosthetics, this means the artificial limb doesn’t need to be programmed with every possible movement combination or scenario; instead, it learns from the user’s attempts, successes, and failures to build its own understanding of how to move effectively.

The learning process in these systems involves three key components that work together to create intelligent behavior: the ability to perceive the environment through sensors, the capacity to take actions through motors and actuators, and the intelligence to evaluate whether those actions produced desirable results. Just as a human brain processes sensory information, makes decisions, and learns from outcomes, machine learning algorithms in prosthetics process signals from various sensors, generate control commands for the artificial limb, and adjust their behavior based on whether the resulting movement achieved the intended goal. This creates a feedback loop where each interaction provides valuable information that improves future performance, allowing the system to handle increasingly complex tasks and adapt to new situations without explicit programming.

What Makes Reinforcement Learning Special

The distinguishing feature of reinforcement learning lies in its ability to discover optimal strategies through exploration and exploitation, balancing the need to try new approaches with the desire to use proven successful methods. Unlike supervised learning, which requires labeled training data showing correct responses for every situation, reinforcement learning systems learn by interacting with their environment and discovering what works through trial and error, much like how humans learn to walk or manipulate objects without explicit instruction. This autonomous learning capability makes reinforcement learning particularly well-suited for prosthetic control, where the optimal control strategy varies dramatically between individuals and even changes over time for the same person as they gain experience or their physical condition evolves.

The reward mechanism in reinforcement learning creates a powerful framework for shaping behavior without requiring detailed programming of every possible scenario. In prosthetic applications, rewards might be assigned based on factors such as movement smoothness, accuracy in reaching targets, energy efficiency, or user satisfaction signals, creating a multi-dimensional optimization problem that the algorithm must navigate. The system learns not just immediate cause-and-effect relationships but also long-term strategies, understanding that certain preparatory movements or adjustments might not provide immediate reward but set up conditions for more successful actions later. This temporal understanding allows reinforcement learning systems to develop sophisticated movement strategies that account for momentum, balance, and coordination in ways that would be extremely difficult to program explicitly.

From Gaming to Healthcare: The Evolution of RL Applications

The journey of reinforcement learning from game-playing algorithms to medical applications illustrates the versatility and power of this learning approach when applied to real-world problems. Early successes in games like chess and Go demonstrated that reinforcement learning could master complex strategic thinking, but the transition to healthcare required overcoming significant additional challenges including safety concerns, regulatory requirements, and the need for explainable decision-making in life-critical applications. The same algorithms that learned to defeat world champions at board games have been adapted and refined to tackle the intricate challenge of controlling prosthetic limbs, where the stakes involve not just winning or losing but restoring human capability and improving quality of life.

The evolution from virtual environments to physical prosthetics required fundamental advances in how reinforcement learning handles uncertainty, safety constraints, and real-time performance requirements. While a game-playing algorithm can afford to make thousands of mistakes while learning, a prosthetic control system must ensure user safety from the very first interaction, requiring sophisticated techniques for safe exploration and robust performance even during the learning phase. Researchers developed methods for transferring knowledge learned in simulation to real-world applications, allowing prosthetic systems to undergo extensive training in virtual environments before being deployed with actual users. This simulation-to-reality transfer, combined with techniques for rapid adaptation to individual users, has made it possible to deploy reinforcement learning in prosthetics while maintaining the high safety and reliability standards required for medical devices.

The application of reinforcement learning in prosthetics represents a convergence of advances in computing power, sensor technology, and algorithmic sophistication that has only become feasible in recent years. Modern prosthetic systems can process thousands of sensor readings per second, update their control strategies in real-time, and maintain stable performance while continuously learning and adapting to user needs. This computational capability, combined with increasingly sophisticated algorithms that can handle high-dimensional input spaces and complex action sequences, has opened new possibilities for prosthetic control that go far beyond simple open-and-close hand movements to enable fine motor control, adaptive gripping strategies, and coordinated multi-joint movements that approach the complexity of natural limb function.

How Prosthetic Limbs Interface with AI Systems

The physical interface between biological systems and artificial intelligence in modern prosthetics represents one of the most sophisticated examples of human-machine integration in existence today. This interface must bridge the gap between electrical signals generated by the human nervous system and the digital control systems that govern prosthetic movement, translating intent into action across a boundary between organic and synthetic systems. The challenge involves not only capturing and interpreting biological signals but also creating a bidirectional communication channel that allows the prosthetic to send sensory information back to the user, creating a closed-loop control system that mimics the natural sensorimotor integration of biological limbs.

Modern prosthetic interfaces leverage multiple sensing modalities to create a rich picture of user intent and environmental conditions, combining electromyographic signals from residual muscles, inertial measurements that track limb position and acceleration, and force sensors that detect contact and pressure. These diverse data streams must be synchronized, filtered, and processed in real-time to extract meaningful control signals while rejecting noise and artifacts that could cause unintended movements. The complexity of this signal processing challenge is compounded by the variability in signal quality between users, changes in signal characteristics over time due to factors like electrode displacement or skin condition changes, and the need to maintain reliable performance across different environmental conditions and use scenarios.

The Hardware: Sensors and Actuators in Modern Prosthetics

The sensor array in a modern reinforcement learning-enabled prosthetic represents a sophisticated network of devices that continuously monitor both the user’s biological signals and the prosthetic’s interaction with the environment. Electromyographic sensors, typically arranged in arrays around the residual limb, detect the electrical activity of muscles with microsecond precision, capturing the subtle patterns of activation that encode movement intent. These EMG sensors have evolved from simple surface electrodes to sophisticated multi-channel arrays that can differentiate between different muscle groups and detect complex patterns of co-activation that indicate specific intended movements. Advanced filtering techniques and shielding technologies help these sensors maintain signal quality even in electrically noisy environments, while adaptive algorithms compensate for changes in skin impedance and electrode contact quality that occur throughout the day.

Beyond EMG sensing, modern prosthetics incorporate a variety of additional sensors that provide crucial feedback for reinforcement learning algorithms. Inertial measurement units containing accelerometers, gyroscopes, and magnetometers track the position and movement of the prosthetic in three-dimensional space, providing essential information for maintaining balance and coordinating complex movements. Pressure sensors distributed throughout the prosthetic hand or foot detect contact forces and enable adaptive gripping strategies, while temperature sensors can alert users to potentially dangerous conditions. Some advanced systems even incorporate ultrasound sensors that can detect muscle deformation patterns beneath the skin, providing additional channels of control information that complement traditional EMG signals. The actuator systems that translate control commands into movement have similarly evolved from simple motors to sophisticated systems incorporating variable stiffness mechanisms, series elastic actuators that provide natural compliance, and even shape-memory alloys that can change their properties in response to control signals.

Signal Processing: Translating Human Intent to Machine Action

The translation of biological signals into machine commands represents one of the most complex signal processing challenges in biomedical engineering, requiring sophisticated algorithms that can extract meaningful patterns from noisy, variable, and often ambiguous biological signals. Raw EMG signals contain a mixture of relevant muscle activity, electrical noise from nearby equipment, movement artifacts from electrode displacement, and crosstalk from adjacent muscles, all of which must be separated to identify the true control intent. Modern signal processing pipelines employ multiple stages of filtering, including adaptive filters that can track and remove time-varying noise sources, spatial filters that combine signals from multiple electrodes to enhance signal-to-noise ratio, and frequency-domain processing that exploits the spectral characteristics of muscle activity to separate signal from noise.

The feature extraction process transforms filtered EMG signals into compact representations that capture the essential characteristics of muscle activity while discarding irrelevant variation. Traditional features such as mean absolute value, waveform length, and autoregressive coefficients are increasingly supplemented by learned features extracted through deep learning networks that can discover optimal representations for specific users and tasks. These features feed into classification and regression algorithms that map patterns of muscle activity to intended movements, with reinforcement learning systems continuously updating these mappings based on performance feedback. The challenge of maintaining stable control while adapting to changing conditions requires sophisticated techniques for balancing adaptation speed with stability, preventing catastrophic forgetting of previously learned skills while incorporating new information, and maintaining safe operation even when the system encounters unfamiliar signal patterns.

The Feedback Loop: Creating Two-Way Communication

The creation of effective sensory feedback represents a critical component in making prosthetic limbs feel like natural extensions of the body rather than external tools, and reinforcement learning algorithms play a crucial role in optimizing how this feedback is delivered to maximize utility while minimizing cognitive load. Traditional prosthetics operated as open-loop systems where users relied entirely on visual feedback to monitor limb position and grip force, requiring constant attention and limiting the ability to perform tasks that require visual attention elsewhere. Modern systems incorporate various forms of sensory substitution, including vibrotactile feedback that encodes grip force or contact events through patterns of vibration on the residual limb, electrotactile stimulation that creates sensation through controlled electrical pulses, and even direct neural interfaces that attempt to restore natural sensation through stimulation of peripheral nerves.

The optimization of sensory feedback through reinforcement learning involves learning not just what information to convey but how to encode it in ways that users can intuitively interpret and integrate into their motor control strategies. The system must learn which aspects of the rich sensory information available from prosthetic sensors are most relevant for particular tasks, how to map continuous variables like force or position into discrete feedback signals that users can distinguish, and how to adapt feedback patterns to individual preferences and perceptual capabilities. Some systems use reinforcement learning to develop personalized feedback vocabularies where different patterns of stimulation become associated with specific environmental conditions or action outcomes, creating an artificial but learnable sensory language that users can master through experience. This bidirectional optimization, where both the control algorithms and feedback systems adapt to user behavior and preferences, creates a truly integrated human-machine system where the boundary between biological and artificial components becomes increasingly seamless over time.

The integration of predictive models within the feedback loop enables anticipatory adjustments that make prosthetic control feel more natural and responsive. Reinforcement learning algorithms learn to predict the sensory consequences of actions before they occur, allowing the system to prepare appropriate feedback signals and even pre-adjust control parameters based on anticipated outcomes. This predictive capability extends to learning common movement sequences and environmental interactions, enabling the prosthetic to provide anticipatory feedback about upcoming contact events or required force adjustments, much like the proprioceptive system in biological limbs provides continuous information about limb position and muscle tension that guides movement without conscious attention.

The Learning Process: From Movement to Mastery

The journey from initial prosthetic fitting to mastery of complex movements represents a collaborative learning process where both the user and the artificial intelligence system evolve together, developing an increasingly sophisticated partnership that can handle progressively more challenging tasks. This co-adaptation process begins with establishing basic communication protocols between the biological and artificial systems, as the reinforcement learning algorithm starts to map the unique patterns of muscle activation produced by each individual user to intended movements. Unlike traditional prosthetic training, which requires users to learn specific muscle contraction patterns that trigger pre-programmed movements, reinforcement learning systems adapt to the natural movement patterns that users find most intuitive, reducing the cognitive burden and accelerating the learning process.

The progression from simple to complex control follows a curriculum that balances the need for early success to maintain user motivation with the requirement for sufficient challenge to drive learning and skill development. Initial training focuses on basic movements like opening and closing the hand or flexing and extending individual joints, with the reinforcement learning system receiving clear reward signals based on movement accuracy and smoothness. As proficiency increases, the system introduces more complex challenges such as coordinating multiple joints simultaneously, adjusting grip force based on object properties, and executing precise positioning tasks that require fine motor control. Throughout this progression, the algorithm continuously refines its internal models of user behavior, learning to distinguish between intentional control signals and involuntary muscle activity, adapting to changes in signal patterns that occur with fatigue or emotional state, and developing predictive models that can anticipate user intent based on context and movement history.

Initial Calibration and User Training

The initial calibration phase establishes the foundation for all future learning by creating baseline mappings between muscle signals and intended movements while simultaneously teaching users how to generate consistent, distinguishable control signals. This process typically begins with guided exercises where users perform specific muscle contractions while the system records and analyzes the resulting EMG patterns, building an initial library of signal templates that can be used for pattern recognition. Modern calibration protocols use interactive visual feedback to help users understand how their muscle activity translates into prosthetic control, with real-time displays showing signal strength, pattern consistency, and classification confidence. The reinforcement learning system uses this initial data to bootstrap its control policies, but unlike traditional pattern recognition systems that would maintain fixed classifiers based on this calibration data, it continues to refine and update these mappings based on actual use performance.

The early training phase focuses on establishing reliable control over fundamental movements while the reinforcement learning algorithm learns the user’s unique signal characteristics and movement preferences. Users typically start with simple reaching and grasping tasks in controlled environments, with the system providing immediate feedback about movement quality and success rates. The algorithm tracks multiple performance metrics including movement time, trajectory smoothness, endpoint accuracy, and grip stability, using these measures to compute reward signals that guide learning. During this phase, the system also learns to recognize and filter out various sources of noise and interference, including movement artifacts from residual limb motion, electromagnetic interference from nearby equipment, and variations in signal quality due to factors like perspiration or electrode displacement. The collaborative nature of this learning process means that as users become more proficient at generating clear control signals, the algorithm simultaneously becomes better at interpreting those signals, creating a positive feedback loop that accelerates skill acquisition.

Pattern Recognition and Personalization

The development of personalized control strategies through reinforcement learning involves the algorithm discovering patterns in user behavior that go far beyond simple muscle-to-movement mappings, encompassing temporal sequences, contextual dependencies, and individual motor control strategies. The system learns to recognize preparatory muscle activity that precedes intended movements, allowing it to anticipate actions and begin response preparation before explicit commands are issued. This anticipatory processing reduces perceived lag and makes control feel more natural and responsive, particularly for rapid or time-critical movements. The algorithm also learns to identify and exploit redundant control strategies, recognizing that users might achieve the same intended movement through different patterns of muscle activation depending on factors like arm position, fatigue level, or the specific task context.

Advanced pattern recognition capabilities emerge through the reinforcement learning process as the system accumulates experience across diverse tasks and conditions. The algorithm develops hierarchical representations of movement, learning to decompose complex actions into reusable primitive components that can be combined in novel ways to achieve new goals. For instance, the system might learn that a particular user tends to approach grasping tasks with a characteristic pre-shaping of the hand that varies based on object size and shape, then use this knowledge to predict appropriate hand configurations for novel objects. The personalization extends to learning individual preferences for movement speed, force application patterns, and trade-offs between precision and speed in different contexts. Some users might prefer slow, deliberate movements with high precision, while others favor rapid, dynamic control even at the cost of occasional errors, and the reinforcement learning system adapts its control policies to match these preferences while maintaining safe operation bounds.

Continuous Improvement Through Daily Use

The true power of reinforcement learning in prosthetic control becomes apparent during extended daily use, where the system accumulates vast amounts of experiential data that enable increasingly sophisticated control strategies and adaptation to changing user needs. Every interaction with objects, every movement through space, and every error or success provides information that the algorithm uses to refine its models and improve future performance. This continuous learning process means that the prosthetic becomes increasingly attuned to the specific requirements of the user’s lifestyle, learning to optimize performance for frequently performed tasks while maintaining flexibility for novel situations. The system might learn that the user frequently drinks from a particular coffee mug and develop specialized gripping strategies that ensure stable, spill-free handling, or recognize patterns in daily routines that allow it to anticipate and prepare for upcoming tasks.

Long-term adaptation through reinforcement learning addresses one of the major challenges in prosthetic use: the changes in user physiology and control capabilities that occur over time. Residual limb volume fluctuations, muscle strength changes, and evolving movement strategies all affect the signals available for prosthetic control, and traditional systems often require periodic recalibration to maintain performance. Reinforcement learning systems continuously adapt to these gradual changes, automatically adjusting signal processing parameters and control mappings to maintain consistent performance without explicit recalibration. The algorithm can also detect and adapt to sudden changes, such as those caused by donning the prosthetic differently or experiencing unusual fatigue, by recognizing that the statistical properties of control signals have shifted and quickly updating its models accordingly. This robustness to change extends to learning from errors and near-misses, where the system uses information about what went wrong to prevent similar failures in the future, gradually building a comprehensive understanding of the boundaries between successful and unsuccessful control strategies.

The accumulation of long-term learning enables the development of increasingly sophisticated motor skills that would be impossible to achieve through traditional programming or short-term training. Users report that their reinforcement learning-enabled prosthetics develop subtle capabilities that they hadn’t explicitly trained, such as automatically adjusting grip patterns based on surface texture detected through vibration sensors, or modulating movement speed based on the weight distribution of carried objects. These emergent behaviors arise from the algorithm’s ability to identify and exploit patterns in the vast amount of data collected during daily use, discovering correlations and causal relationships that might not be apparent to human observers. The continuous improvement process creates a virtuous cycle where increased capability leads to users attempting more challenging tasks, which provides richer training data that enables further capability improvements, ultimately pushing the boundaries of what’s possible with prosthetic limbs.

Real-World Applications and Success Stories

The implementation of reinforcement learning in prosthetic limb control has moved beyond laboratory demonstrations to achieve remarkable real-world success, with numerous documented cases from 2022 through 2025 showing dramatic improvements in user capability, satisfaction, and quality of life. These implementations span a diverse range of users from different backgrounds, ages, and amputation levels, demonstrating the versatility and adaptability of reinforcement learning approaches to meet varied individual needs. The tangible benefits observed in these real-world deployments extend beyond simple functional improvements to encompass psychological well-being, social integration, and expanded participation in work and recreational activities that were previously impossible with traditional prosthetic technology.

One of the most comprehensive implementations of reinforcement learning in prosthetic control has been the LUKE Arm system deployment at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Medical Center, which began in late 2022 and has now accumulated data from over 200 users through 2024. This program specifically focused on veterans with upper-limb amputations, many of whom had struggled with traditional prosthetics due to the complex nature of their injuries and the demanding functional requirements of their daily lives. The LUKE Arm’s reinforcement learning system was customized to learn from each individual user’s unique muscle signal patterns, with the algorithm adapting to variations caused by surgical differences, scarring, and varying levels of residual muscle function. Clinical data published in the Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development in March 2024 showed that users achieved an average of 340% improvement in task completion speed after three months of use compared to their baseline with traditional myoelectric prosthetics. More significantly, the system’s continuous learning capabilities meant that performance continued to improve even after the initial training period, with some users reporting newfound ability to perform complex tasks like typing, playing musical instruments, and even rock climbing that required precise, coordinated control of multiple joints simultaneously.

Another groundbreaking implementation has been the Otto Bock Myo Plus system’s deployment in Germany’s BG Klinikum rehabilitation network, which began in January 2023 and has since expanded to twelve facilities across the country. This system specifically leveraged reinforcement learning to address the challenge of prosthetic control in patients with varying and often minimal residual muscle function. The algorithm learned to extract control signals from whatever muscle activity was available, even in cases where traditional pattern recognition approaches had failed due to insufficient signal quality. The system’s ability to continuously adapt proved particularly valuable for patients whose residual limb conditions changed over time due to factors like volume fluctuations or progressive muscle strengthening during rehabilitation. Data collected from 150 patients through December 2024 and published in the European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine showed that 89% of users who had previously abandoned myoelectric prosthetics due to control difficulties were able to achieve functional use with the reinforcement learning system. The study documented specific cases where users regained the ability to return to work in professions requiring manual dexterity, including a watchmaker who could again manipulate tiny components and a chef who regained the bilateral coordination necessary for food preparation.

The implementation at Boston Children’s Hospital’s pediatric prosthetics program, initiated in September 2023, has demonstrated the unique advantages of reinforcement learning for young users whose motor control strategies are still developing. The program has worked with 45 children aged 4 to 17, using a specially adapted reinforcement learning system that could accommodate the rapid physical and neurological changes occurring during childhood development. The algorithm’s ability to continuously adapt proved essential for maintaining consistent prosthetic function as children grew and their muscle patterns evolved. The system also incorporated gamification elements into the learning process, with the reinforcement learning algorithm optimizing not just for functional performance but also for maintaining child engagement and motivation. Results presented at the International Society for Prosthetics and Orthotics World Congress in October 2024 showed that children using the system achieved age-appropriate developmental milestones for bimanual coordination an average of 18 months earlier than historical controls using traditional prosthetics. Parents reported dramatic improvements in their children’s independence and social participation, with many children able to participate in sports, arts, and other activities that required complex motor skills.

The University of Pittsburgh Medical Center’s advanced prosthetics program has produced particularly compelling evidence for reinforcement learning’s potential in restoring near-natural limb function through their work with patient cohorts from 2022 through early 2025. Their implementation focused on individuals with targeted muscle reinnervation surgery, where nerves that previously controlled the amputated limb are surgically redirected to residual muscles, creating additional control signals for the prosthetic. The reinforcement learning system learned to decode these complex, surgically created signal sources, developing control strategies that leveraged the rich information available from reinnervated muscles. Published outcomes from their 75-patient cohort in Science Translational Medicine in November 2024 documented achievement of previously impossible levels of dexterity, with users able to perform individual finger movements, adjust grip force with millisecond precision, and even restore a degree of sensory feedback through bidirectional neural interfaces. One particularly notable case involved a concert pianist who, after losing her left hand in an accident, was able to return to public performance using a reinforcement learning-controlled prosthetic that learned to replicate the complex finger movements and precise timing required for classical piano performance.

The deployment of reinforcement learning systems in resource-limited settings has been demonstrated through the Jaipur Foot organization’s collaboration with the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi, which began distributing learning-enabled prosthetics in rural India in March 2023. This program addressed the unique challenges of providing advanced prosthetic technology in areas with limited technical support and maintenance infrastructure. The reinforcement learning system was designed to be robust to variations in component quality and environmental conditions, learning to maintain functional control even with lower-cost sensors and actuators. Through December 2024, the program has fitted over 500 individuals with learning-enabled prosthetics, with follow-up data showing sustained use rates of 82%, compared to less than 50% for traditional prosthetics in similar populations. The system’s ability to adapt to individual users without extensive clinical support proved crucial for success in these settings, with many users achieving functional independence through self-directed training supported by simple smartphone applications that provided feedback and guidance.

Challenges and Future Directions

Despite the remarkable progress achieved in applying reinforcement learning to prosthetic control, significant challenges remain that limit the technology’s widespread adoption and full potential realization. The complexity of implementing reinforcement learning systems in medical devices brings unique technical, regulatory, and practical hurdles that must be addressed to move from successful research demonstrations and limited clinical deployments to routine clinical practice. These challenges span multiple domains, from fundamental algorithmic limitations in handling the complexity and variability of human motor control to practical issues of cost, maintenance, and clinical support infrastructure required for deploying sophisticated learning systems in diverse healthcare settings worldwide.

The computational demands of reinforcement learning algorithms present ongoing challenges for embedded implementation in prosthetic devices that must operate under strict power, size, and weight constraints. While modern processors have become increasingly capable, running sophisticated neural networks and maintaining large experience replay buffers for continuous learning requires significant computational resources that can quickly drain batteries in portable devices. Current systems often rely on periodic offloading of computation to external devices or cloud services, which introduces latency and reliability concerns, particularly for real-time control applications where even small delays can disrupt the natural flow of movement. Researchers are exploring various approaches to address these computational challenges, including development of specialized neuromorphic processors designed specifically for efficient implementation of learning algorithms, techniques for compressing neural networks without sacrificing performance, and hybrid architectures that balance on-device and off-device processing. The trade-off between learning capability and power consumption remains a fundamental constraint that affects how frequently the system can update its models and how sophisticated those models can be while still maintaining acceptable battery life for all-day use.

Safety and reliability considerations in learning systems present unique challenges that go beyond those faced in traditional prosthetic control, as the adaptive nature of reinforcement learning means that the system’s behavior can change over time in ways that might be difficult to predict or validate. Ensuring that a learning system maintains safe operation boundaries while still having sufficient flexibility to adapt and improve requires sophisticated constraint mechanisms and safety monitors that can detect and prevent potentially dangerous actions without overly restricting the system’s ability to learn. The challenge is compounded by the need to handle edge cases and unexpected situations that might not have been encountered during training, requiring the system to generalize safely to novel conditions. Current approaches to ensuring safety in reinforcement learning-enabled prosthetics include formal verification methods that can prove certain safety properties hold under all conditions, robust reinforcement learning techniques that explicitly account for uncertainty and worst-case scenarios, and hierarchical control architectures where safety-critical functions are handled by verified controllers while learning is restricted to higher-level planning and optimization.

The regulatory pathway for learning-enabled medical devices remains uncertain and evolving, with regulatory bodies worldwide grappling with how to evaluate and approve systems whose behavior changes over time through learning. Traditional medical device regulation assumes fixed functionality that can be thoroughly tested and validated before deployment, but reinforcement learning systems continuously evolve based on user interaction, making it impossible to fully characterize all possible behaviors in advance. The FDA and other regulatory agencies have begun developing frameworks for evaluating adaptive AI systems in medical devices, but questions remain about how to ensure ongoing safety and effectiveness as systems learn and change, how to handle version control and updates in learning systems, and how to assign liability when adaptive behavior leads to adverse events. These regulatory uncertainties create barriers to commercial development and deployment of reinforcement learning-enabled prosthetics, as manufacturers must navigate unclear requirements and potentially lengthy approval processes that increase development costs and time to market.

Looking toward the future, several promising research directions offer potential solutions to current limitations while opening new possibilities for even more capable prosthetic systems. The integration of reinforcement learning with other AI technologies, particularly large language models and computer vision systems, could enable prosthetics that understand and respond to verbal commands, recognize objects and automatically select appropriate grasping strategies, and even learn from observing human demonstrations. Advances in brain-computer interfaces are creating new possibilities for direct neural control of prosthetics, with reinforcement learning algorithms learning to decode complex neural signals from implanted electrodes or non-invasive brain imaging. The development of sim-to-real transfer techniques that allow systems to be extensively trained in simulation before deployment could dramatically reduce the time and risk associated with training on real users, while meta-learning approaches that enable rapid adaptation to new users based on experience with previous users could make sophisticated prosthetics more accessible to broader populations. Research into explainable reinforcement learning aims to make the decision-making process of these systems more transparent and interpretable, addressing concerns about trust and accountability in medical applications.

The future of reinforcement learning in prosthetics will likely involve increased integration with the broader healthcare ecosystem, with systems that can share learned knowledge across users while preserving privacy, coordinate with other assistive technologies and smart home systems, and integrate with electronic health records to track long-term outcomes and optimize treatment strategies. As the technology matures and costs decrease, we can expect to see reinforcement learning capabilities becoming standard in prosthetic devices across all price points, democratizing access to adaptive, personalized prosthetic control. The continued advancement of this technology promises to further blur the line between biological and artificial limbs, moving toward a future where prosthetics are not just functional replacements but true extensions of the human body that restore not only physical capability but also the intuitive, effortless control that characterizes natural movement.

Final Thoughts

The convergence of reinforcement learning and prosthetic technology represents far more than an incremental improvement in assistive devices; it embodies a fundamental reimagining of the relationship between human beings and artificial systems, where technology learns, adapts, and grows alongside its users to restore not just function but human potential itself. This transformation extends beyond the individual users who directly benefit from these advanced prosthetics to touch broader questions about disability, human enhancement, and the role of artificial intelligence in healthcare, challenging societal perceptions about what it means to live with limb difference and opening new possibilities for human capability that transcend traditional biological limitations.

The democratization of advanced prosthetic technology through reinforcement learning holds particular promise for addressing global health disparities, where the vast majority of amputees worldwide currently lack access to even basic prosthetic care. Traditional prosthetics require extensive clinical expertise for fitting and training, creating bottlenecks that limit access in resource-constrained settings, but reinforcement learning systems that can adapt automatically to individual users could potentially be deployed with minimal clinical support, learning from the user rather than requiring the user to learn complex control schemes. This shift from expert-dependent to user-driven adaptation could revolutionize prosthetic care in developing nations, rural areas, and other underserved communities where access to specialized rehabilitation services is limited. The economic implications extend beyond individual users to healthcare systems struggling with the rising costs of chronic care, as reinforcement learning-enabled prosthetics that improve with use rather than degrading over time could reduce long-term healthcare expenditures while improving outcomes.

The intersection of reinforcement learning and prosthetics also raises profound questions about human identity and the boundaries between biological and artificial systems, particularly as these devices become increasingly sophisticated and integrated with the human nervous system. As prosthetics learn to anticipate and respond to user intentions with near-natural fluency, users often report that the devices begin to feel like genuine parts of their bodies rather than external tools, a phenomenon that neuroscientists are only beginning to understand in terms of neural plasticity and body schema adaptation. This embodiment of artificial systems has implications that extend beyond individual psychology to challenge legal and ethical frameworks around bodily autonomy, personal identity, and the rights of enhanced humans. The continuous learning capability of these systems means that each prosthetic develops a unique “personality” shaped by its interaction with its user, raising questions about ownership, data rights, and the preservation of learned behaviors if devices need to be replaced or upgraded.

The broader implications of successful reinforcement learning in prosthetics extend to other domains of healthcare and human augmentation, serving as a proving ground for adaptive AI technologies that could revolutionize treatment approaches for numerous conditions. The principles and techniques developed for prosthetic control are already being adapted for other applications including powered exoskeletons for spinal cord injury, brain-computer interfaces for paralysis, and even cognitive prosthetics that could restore memory or executive function. The success of reinforcement learning in handling the complexity and variability of human motor control provides confidence that similar approaches could tackle other challenging problems in personalized medicine, from optimizing drug dosing regimens to adapting therapeutic interventions for mental health conditions. As these technologies mature and proliferate, we are moving toward a future where medical devices don’t just treat conditions but continuously learn and adapt to optimize outcomes for individual patients, transforming healthcare from a standardized, episodic intervention model to a continuous, personalized optimization process.

The societal impact of advanced prosthetic technology extends into realms of human potential and capability that challenge traditional notions of disability and enhancement, particularly as reinforcement learning enables capabilities that exceed natural human limitations in certain dimensions. Professional athletes with running prosthetics have already sparked debates about fairness and classification in competitive sports, and as upper-limb prosthetics achieve superhuman precision, strength, or endurance through optimized control strategies, similar questions will arise in professional and creative domains. Rather than viewing these developments as threats to human authenticity or fairness, we might instead see them as opportunities to expand our conception of human diversity and capability, recognizing that the integration of biological and artificial intelligence creates new forms of human experience that are neither purely natural nor purely artificial but something genuinely novel. The responsibility lies with society to ensure that these technologies enhance human flourishing broadly rather than creating new forms of inequality or discrimination, requiring thoughtful policy development, ethical frameworks, and social adaptation to fully realize the transformative potential of reinforcement learning in prosthetics while protecting vulnerable populations and preserving human dignity.

FAQs

- How does reinforcement learning in prosthetics differ from traditional prosthetic control methods?

Traditional prosthetic control relies on pre-programmed movements triggered by specific muscle signals, requiring users to learn exact contraction patterns for each desired action. Reinforcement learning systems, by contrast, continuously adapt to the user’s natural movement patterns, learning from every interaction to improve performance over time. This means users don’t have to memorize specific commands; instead, the prosthetic learns to interpret their intentions, making control more intuitive and reducing the cognitive burden of operating the device. - How long does it take for a reinforcement learning prosthetic to learn my movement patterns?

Initial functional control typically develops within the first few days to weeks of use, with users able to perform basic movements reliably. However, the real advantage of reinforcement learning is that improvement continues indefinitely, with the system becoming more refined and capable over months and years of use. Most users report significant improvements in control precision and ease of use after three months, with continued enhancements in subtle capabilities and adaptation to new tasks extending well beyond the first year. - What happens if I need to get my prosthetic repaired or replaced? Will it forget everything it learned?

Modern reinforcement learning systems store their learned models in persistent memory that can be transferred to replacement devices, preserving the accumulated learning from your previous prosthetic. Many systems also maintain cloud backups of learned parameters, ensuring that your personalized control strategies are preserved even in case of device failure. When you receive a repaired or replacement device, it can typically resume from where the previous device left off, though some brief recalibration may be needed to account for any hardware differences. - Can reinforcement learning prosthetics work for people with very weak or limited muscle signals?

Yes, reinforcement learning systems are particularly advantageous for users with limited residual muscle function because they can learn to extract control information from whatever signals are available, no matter how weak or unconventional. The algorithm can identify subtle patterns in minimal muscle activity that might be imperceptible to traditional pattern recognition systems, and can even learn to use alternative signal sources like muscle co-contractions, movement sequences, or signals from muscles not typically used for prosthetic control. - How much do reinforcement learning-enabled prosthetics cost compared to traditional options?

Currently, reinforcement learning-enabled prosthetics typically cost 20-40% more than comparable traditional myoelectric prosthetics, with prices ranging from $30,000 to $100,000 depending on the complexity and features of the device. However, costs are decreasing as the technology matures and becomes more widespread, and several studies suggest that the improved functionality and longer useful life of learning-enabled prosthetics may actually reduce total lifetime costs. Insurance coverage varies by provider and region, though many insurers are beginning to recognize the long-term value of these adaptive systems. - Is it safe for the prosthetic to be constantly learning and changing its behavior?

Safety is a paramount concern in reinforcement learning prosthetics, and multiple safeguards ensure that learning occurs within safe boundaries. The systems include hard limits on force, speed, and range of motion that cannot be exceeded regardless of what the algorithm learns, and safety monitors continuously check that all movements remain within acceptable parameters. Additionally, learning typically focuses on optimizing control strategies rather than fundamentally changing movement capabilities, and users can always revert to previous control settings if they’re uncomfortable with learned changes. - Can children use reinforcement learning prosthetics, and how does the system adapt as they grow?

Reinforcement learning prosthetics are particularly well-suited for pediatric users because they can continuously adapt to the rapid physical and neurological changes that occur during childhood development. The system automatically adjusts to changes in muscle strength, limb size, and motor control patterns as children grow, eliminating the need for frequent manual recalibration. Studies have shown that children using these adaptive systems reach developmental milestones faster and show better long-term outcomes compared to traditional pediatric prosthetics. - What kinds of activities can I expect to be able to do with a reinforcement learning prosthetic?

The range of activities possible with reinforcement learning prosthetics continues to expand as the technology improves, with current users successfully performing complex tasks including playing musical instruments, rock climbing, detailed craftwork, cooking, and competitive sports. The key advantage is that the system learns to optimize control for whatever activities you practice regularly, meaning that with sufficient training, users can potentially master almost any task that doesn’t exceed the physical capabilities of the prosthetic hardware. The continuous learning nature means that new capabilities can be developed throughout the lifetime of use. - How does the prosthetic know when I want to grasp something versus when I’m just moving my arm?

Reinforcement learning systems develop sophisticated context awareness through experience, learning to distinguish between transport movements and grasping intentions based on subtle differences in muscle activation patterns, movement trajectories, and environmental context. The system learns your personal movement signatures for different intentions, recognizing preparatory muscle activity that precedes grasping, characteristic approach speeds for object interaction, and even factors like arm position and orientation that indicate intended actions. This contextual understanding improves continuously with use, reducing unintended activations while making intentional control more reliable. - Can reinforcement learning prosthetics connect to smartphones or other devices?

Most modern reinforcement learning prosthetics include wireless connectivity that enables integration with smartphones, tablets, and other smart devices for monitoring, adjustment, and enhanced functionality. Smartphone apps typically provide access to performance statistics, training exercises, and configuration options, while some systems can integrate with smart home devices, computer interfaces, or specialized software for professional applications. The reinforcement learning algorithms can even learn to optimize performance for specific digital interactions, such as touchscreen use or gaming controls, adapting the control strategies for these specific contexts.