The blockchain revolution has brought transformative technologies that promise to reshape digital transactions, data storage, and trust in distributed systems. Yet the technology faces a fundamental challenge called the blockchain trilemma, suggesting it is nearly impossible to simultaneously achieve high levels of decentralization, security, and scalability. As networks grow and transaction volumes increase, this limitation manifests through congested networks, slow transaction times, and prohibitively high fees that make many applications impractical.

Traditional blockchain architectures process transactions sequentially through a single chain where every node must validate every transaction. This ensures security and consistency but creates severe bottlenecks as usage grows. Bitcoin processes approximately seven transactions per second, while Ethereum manages around fifteen. These figures pale compared to traditional payment processors like Visa, which handles thousands of transactions per second. This disparity presents a critical obstacle to blockchain achieving mainstream adoption for high-volume applications.

Sharding has emerged as one of the most promising solutions to blockchain scalability challenges. Drawing from database sharding techniques used in distributed systems for decades, blockchain sharding divides the network into smaller partitions called shards. Each shard maintains its own subset of the blockchain state and processes transactions in parallel with other shards. This horizontal partitioning allows networks to process multiple transactions simultaneously across different shards, dramatically increasing overall throughput.

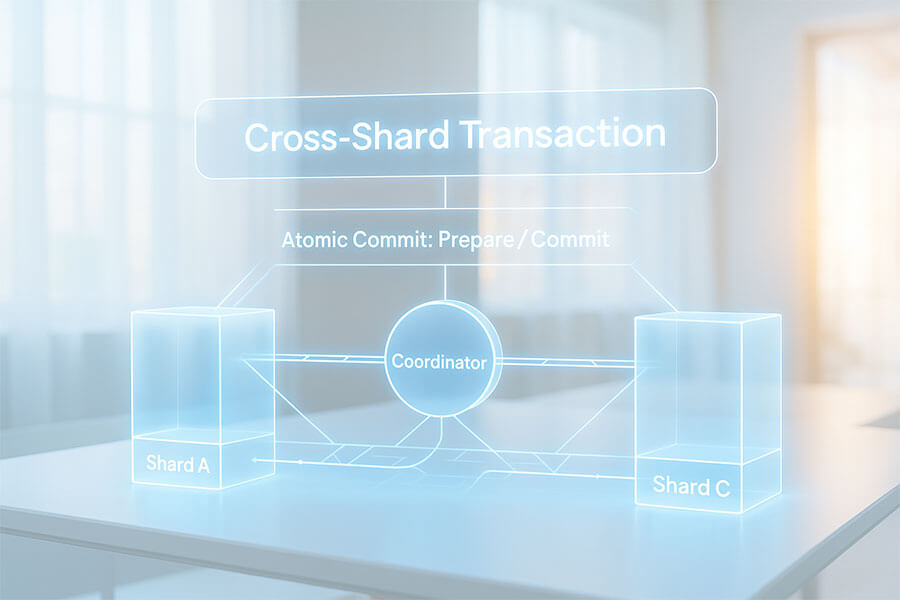

However, sharding creates complex challenges that must be addressed to maintain security and consistency properties. The most significant involves cross-shard transactions, which require reading or writing data across multiple shards. When users transfer assets between accounts on different shards, or when smart contracts need to interact across shards, the system must coordinate while maintaining critical properties like atomicity and consistency.

Atomicity ensures transactions either complete entirely or have no effect at all, preventing partial operation completions. Consistency guarantees the blockchain always transitions from one valid state to another, ensuring rules like value conservation are never violated. These properties are straightforward in single-chain architectures where validators see all transactions in the same order, but become significantly more complex when state is partitioned across independently operating shards.

The technical approaches to handling cross-shard transactions represent sophisticated blockchain innovations. These methods must balance transaction latency, communication overhead between shards, resistance to attack vectors, and implementation complexity. Different blockchain platforms have taken varying approaches, each making different trade-offs between performance, security, and ease of implementation.

This article explores cross-shard transaction processing, examining fundamental concepts, coordination mechanisms, real-world implementations, and associated benefits and challenges. Through detailed analysis of how leading platforms address cross-shard transaction challenges, we develop comprehensive understanding of both theoretical foundations and practical realities of building scalable blockchain systems that maintain security and consistency properties users depend upon.

Understanding Blockchain Sharding Fundamentals

Blockchain sharding represents a fundamental departure from traditional single-chain architecture. To appreciate innovations in cross-shard transaction processing, we must understand what sharding entails, why it has become necessary, and how it changes distributed ledger system operations. The concept draws from decades of distributed database research, but applying these principles to blockchain networks introduces unique challenges stemming from adversarial environments and decentralized trust assumptions.

In traditional blockchain architecture, every full node maintains a complete copy of the entire blockchain state. When a transaction is broadcast, all nodes must validate it and update their local state copies. This provides strong security guarantees since attackers would need to compromise a majority of all nodes. It ensures perfect consistency as all honest nodes maintain identical ledger views. However, this severely limits scalability because the network can only process transactions as fast as individual nodes can validate them, and every node must process every transaction regardless of relevance to its users.

Sharding fundamentally changes this model by partitioning blockchain state across multiple independent shards, each operating like a mini-blockchain within the larger network. The global state is divided among shards, with each shard maintaining and processing transactions affecting its assigned state portion. For example, user accounts might be distributed across shards based on account addresses, so accounts with certain address patterns are assigned to one shard while others go to different shards. This allows different shards to process transactions involving their respective accounts in parallel, multiplying overall transaction processing capacity.

Sharding Concepts and Scalability Needs

The terminology around blockchain sharding encompasses several key concepts essential to understanding system operations. A shard is a partition of the overall network that maintains its own state subset and processes transactions affecting that state. Each shard typically has its own validators who propose blocks, validate transactions, and reach consensus. Validator assignment to shards is typically random and rotated periodically to prevent attackers from targeting specific shards.

State sharding refers to dividing blockchain state data across shards, so different accounts, smart contracts, and state information reside on different shards. This provides greatest scalability benefits but introduces complexity because transactions needing to access or modify state on multiple shards require special cross-shard coordination protocols. Network sharding partitions the network of nodes into smaller groups processing transactions in parallel, but may not involve state partitioning itself. Transaction sharding distributes transaction load across shards without necessarily sharding the state, which simplifies design but provides more limited scalability benefits.

Scalability bottlenecks in traditional blockchain architectures are multifaceted. Computational limitations arise because every node must execute every transaction to verify validity and update state. As transaction volumes increase, nodes require increasingly powerful hardware. Storage challenges emerge as blockchain state grows over time, eventually requiring terabytes of data. Network constraints occur because every transaction must be broadcast to all nodes, creating bandwidth requirements that scale with both transaction count and node count.

Sharding addresses these bottlenecks by distributing computational, storage, and network load across multiple partitions. Computational requirements decrease because validators only process transactions affecting their assigned shard. Storage requirements reduce since shard validators only maintain their shard’s state. Network bandwidth consumption per node decreases because nodes primarily communicate with other validators in their shard. These improvements allow sharded blockchains to achieve throughput scaling roughly linearly with shard count, at least for single-shard transactions.

However, this increased scalability comes with significant trade-offs. Security per shard is potentially lower because each shard is secured by only a fraction of total validators. If attackers concentrate enough malicious validators in a single shard, they might compromise that shard’s integrity even controlling only a small network fraction. This vulnerability is addressed through random validator assignment, frequent rotation between shards, and mechanisms allowing the broader network to detect and respond to shard misbehavior. Cross-shard communication introduces latency and complexity because coordinating transactions spanning multiple shards requires additional communication rounds and consensus, potentially negating some performance benefits that sharding provides for simple intra-shard transactions.

The fundamental challenge of maintaining global consistency when state is partitioned across shards cannot be overstated. In single-chain blockchains, there is unambiguous ordering of all transactions and state transitions. Every node knows precisely the current state because they all process the same transactions in the same order. With sharding, different shards process different transactions in parallel, and there is no single global ordering. This creates potential for inconsistencies and conflicts that must be carefully managed through sophisticated cross-shard transaction protocols ensuring atomicity and maintaining important invariants like value conservation.

Cross-Shard Transaction Mechanics

Understanding how cross-shard transactions work requires examining the entire transaction lifecycle from user creation through validation, execution, and final blockchain commitment. Cross-shard transactions are fundamentally more complex than single-shard transactions because they require coordination between multiple independent network partitions, each potentially validating different concurrent transaction sets. The mechanisms enabling this coordination while maintaining consistency and atomicity represent sophisticated aspects of sharded blockchain design.

When users initiate cross-shard transactions, they create transactions specifying operations affecting state on multiple shards. For example, users might transfer tokens from accounts on shard A to accounts on shard B, or smart contracts on shard C might need to read data from and write data to contracts on both shards D and E. The transaction broadcasts to the network where it must reach validators of all affected shards. Unlike single-shard transactions processed by one validator set, cross-shard transactions require coordination among multiple validator sets, each validating transaction aspects affecting their shard’s state.

Transaction coordinators become crucial in managing this distributed validation process. Depending on the protocol, coordination might be handled by validators of one shard taking the lead, by a special coordination chain or layer, or through distributed protocols where all involved shards participate symmetrically. Coordinators orchestrate transaction execution phases, collect votes or confirmations from participating shards, and ultimately determine whether transactions should be committed or aborted. This coordination must prevent various attack scenarios while maintaining high performance and avoiding centralized failure points that could compromise system security or availability.

Cross-shard transactions introduce significant additional communication overhead compared to single-shard transactions. For single-shard transactions, validators within that shard reach consensus through their local consensus protocol, typically requiring one or two communication rounds. Cross-shard transactions require multiple additional rounds between shards to coordinate execution. Messages must be sent from coordinators to participating shards, responses collected and processed, and depending on protocol, additional confirmation rounds may be necessary to ensure all shards have reached agreement on committing or aborting transactions.

Atomic Commitment Protocols

Atomic commitment is fundamental for cross-shard transactions because it ensures multi-shard operations either complete entirely across all affected shards or have no effect on any shard. Without atomicity, cross-shard transfers could potentially deduct tokens from sender accounts on one shard without crediting recipient accounts on another, violating value conservation. Similarly, smart contract operations that should atomically read and update state on multiple shards could leave systems in inconsistent states if only some effects are applied. Atomic commitment protocols provide mechanisms necessary to prevent these failure scenarios while allowing efficient processing of valid cross-shard transactions.

Two-phase commit protocol provides a classic approach to achieving atomic commitment in distributed systems and forms the basis for many blockchain cross-shard transaction protocols. In the prepare phase, transaction coordinators send prepare messages to all shards involved in transactions. Each shard validates transactions against local state, checking that preconditions are met and execution would result in valid state transitions. If validation succeeds, shards vote to commit transactions and lock relevant state to prevent conflicting transactions from modifying it. If validation fails at any shard, that shard votes to abort. Coordinators collect votes from all participating shards and make commit decisions based on whether all shards voted to commit.

In the commit phase, coordinators send commit decisions to all participating shards. If all shards voted to commit, coordinators send commit messages instructing each shard to apply transaction effects and release locks. If any shard voted to abort or if coordinators don’t receive responses within timeout periods, coordinators send abort messages instructing all shards to discard transactions and release locks without applying effects. Once shards receive coordinator decisions, they execute decisions and acknowledge completion. Transactions are considered complete once all shards have acknowledged executing coordinator decisions.

While two-phase commit provides strong atomicity guarantees, it suffers from a significant blocking problem. If coordinators fail after sending prepare messages but before sending commit or abort messages, participating shards are left holding locks on resources without knowing whether to commit or abort. These shards must wait until coordinators recover or timeouts expire before proceeding, during which time they cannot process other transactions that conflict with locked state. This blocking behavior can significantly reduce system availability and throughput, especially in blockchain contexts where validator nodes may frequently go offline or become unreachable due to network partitions.

Three-phase commit addresses two-phase commit’s blocking problem by adding an additional phase. After collecting votes in the prepare phase but before making final commit decisions, coordinators enter pre-commit phases where they inform all participants they have decided to commit transactions but have not yet done so. Participants acknowledge pre-commit messages and wait for final commit messages. This additional phase allows systems to make progress even if coordinators fail at certain protocol points, because participants can infer coordinator decisions based on the latest phase they reached. However, three-phase commit introduces additional latency due to extra communication rounds and can still block under certain network partition scenarios, making it less commonly used in blockchain systems where network conditions can be unreliable.

Coordination Mechanisms

Specific mechanisms used to coordinate cross-shard transactions vary significantly across blockchain platforms, each making different trade-offs between complexity, performance, and security. Synchronous coordination approaches require all participating shards to coordinate state transitions in lockstep, ensuring strong consistency but potentially limiting throughput when cross-shard transactions are frequent. Asynchronous coordination allows shards to process transactions more independently, using message passing to communicate state changes. This can provide better performance but requires more sophisticated protocols to ensure consistency and handle edge cases.

Many sharded blockchain designs employ beacon chains or relay chains serving as coordination layers for cross-shard communication. Beacon chains maintain metadata about all shards, including current validators, current state roots, and information about cross-shard messages. When transactions on one shard produce output needing consumption by another shard, the sending shard includes messages describing this output in blocks posted to beacon chains. Receiving shards monitor beacon chains for addressed messages, and once they observe finalized messages, they can safely process messages and update local state. Beacon chains act as trusted sources of truth about messages sent between shards and ensure messages are delivered exactly once in consistent order.

Cross-shard messaging protocols define specific formats and semantics of messages that shards exchange to coordinate transaction execution. These protocols must handle various scenarios including simple value transfers between accounts on different shards, smart contract calls spanning multiple shards, and complex transaction workflows involving reading state from some shards and writing state to others. Message formats typically include information about source and destination shards, specific operations to be performed, any data or value being transferred, and cryptographic proofs allowing receiving shards to verify message authenticity without trusting sending shards or intermediaries.

Different blockchain platforms handle coordination reflecting their overall architectural philosophies and priorities. Some platforms prioritize simplicity and security by limiting cross-shard transactions to relatively simple operations like value transfers, avoiding the complexity of general cross-shard smart contract calls. Others aim for maximum expressiveness by supporting arbitrary cross-shard operations but accept additional complexity and potential performance overhead. Some designs use specialized transaction types or smart contract interfaces specifically for cross-shard operations, while others try making cross-shard transactions transparent to users and developers by handling coordination at lower protocol layers.

Cross-shard coordination efficiency has enormous implications for practical performance of sharded blockchain systems. If cross-shard transactions are common and coordination is expensive, the overhead of managing these transactions can consume much of the performance benefit that sharding provides. Some applications naturally partition well, with most transactions affecting state within single shards and only occasional cross-shard interactions, while others require frequent cross-shard communication that can create bottlenecks. Understanding these patterns and designing both blockchain protocols and applications to minimize expensive cross-shard operations is crucial for realizing the full scalability potential of sharded architectures.

Techniques for Consistency and Atomicity

Maintaining ACID properties in sharded blockchain environments presents formidable technical challenges that have driven extensive distributed systems protocol research and innovation. The acronym ACID encompasses atomicity, consistency, isolation, and durability, fundamental properties that database systems and blockchain networks must maintain to ensure correctness and reliability. In traditional single-chain blockchains, these properties emerge naturally from sequential transaction processing and the fact that all validators maintain identical state copies. Sharding disrupts these guarantees by partitioning state and processing transactions in parallel across multiple independent shards, requiring sophisticated techniques to maintain correctness while achieving scalability benefits.

Consistency models define what guarantees systems provide about operation visibility and ordering. Strong consistency models like linearizability provide the strongest guarantees, ensuring operations appear to occur instantaneously at some point between their invocation and response, and that all nodes agree on a single global ordering. This is the consistency model provided by traditional blockchain systems where all validators process the same transactions in the same order. Sharded systems often relax consistency guarantees for operations that can be processed independently while maintaining strong consistency for operations requiring cross-shard coordination. The challenge is determining which operations require coordination and implementing efficient protocols providing appropriate guarantees for each operation type.

Consensus mechanisms adapted for cross-shard scenarios must balance the need for agreement among validators within individual shards with coordination across shards. Intra-shard consensus allows validators within shards to agree on transactions to include in blocks and resulting state transitions using protocols similar to those used in traditional blockchains. Inter-shard consensus coordinates state transitions spanning multiple shards, ensuring cross-shard transactions are processed consistently and atomically. The interaction between these two consensus levels must be carefully designed to prevent various attack scenarios while maintaining good performance characteristics.

Lock-Based and Optimistic Approaches

Pessimistic locking mechanisms prevent conflicts by requiring transactions to acquire locks on all resources they will access before executing. When cross-shard transactions begin execution, they must first acquire locks on relevant state on all participating shards. Only after all locks have been successfully acquired can transactions proceed with reading and modifying state. This approach guarantees conflicting transactions cannot execute concurrently, ensuring isolation and preventing race conditions that could lead to inconsistent state. Once transactions complete, they release all locks, allowing blocked transactions to proceed.

The primary advantage of pessimistic locking is conceptual simplicity and strong guarantees it provides. Developers can reason about transaction execution without worrying about complex conflict scenarios because locking protocols ensure transactions execute as if serialized. However, pessimistic locking has significant performance and availability drawbacks. Holding locks across shards for transaction execution duration can create substantial contention, especially when cross-shard transactions are common. If transactions need to acquire locks on many shards or if locks are held for extended periods due to slow network communication, other transactions may be blocked for unacceptably long times.

The blocking nature of pessimistic locking becomes particularly problematic in blockchain contexts where network conditions can be unpredictable and validator nodes may temporarily become unreachable. If transactions acquire locks on several shards but then coordinators fail before releasing those locks, affected shards may be unable to process other transactions that conflict with locked state until timeouts expire. Deadlock scenarios can also arise when multiple transactions each hold some locks and are waiting to acquire locks held by others, requiring deadlock detection and resolution mechanisms that add further complexity.

Optimistic concurrency control takes a fundamentally different approach by allowing transactions to execute without acquiring locks, operating on the assumption that conflicts will be rare. Transactions read state from shards, perform computations, and prepare to commit state changes. Only at commit time does the system check whether any conflicts occurred by verifying that state the transaction read has not been modified by concurrent transactions. If no conflicts are detected, transactions commit successfully. If conflicts are detected, transactions abort and must be retried. This approach can provide much better performance than pessimistic locking when conflicts are genuinely rare because transactions don’t need to wait for locks and can execute in parallel even if they access overlapping state.

Timestamp ordering provides another technique for managing concurrent transactions without explicit locking. Each transaction is assigned a timestamp when it begins execution, and systems ensure transactions appear to execute in timestamp order. When transactions read or write state, systems check whether operations are consistent with timestamp ordering constraints. If transactions try to read state written by future transactions or write state read or written by future transactions, systems detect ordering violations and may abort transactions. This approach can provide good performance for certain workloads while ensuring serializability, though it requires careful timestamp management and sophisticated protocols for handling aborts and retries.

Consensus Across Shards

Achieving consensus when validators in different shards must agree on transaction outcomes requires coordination protocols that can operate efficiently despite the distributed nature of sharded systems. The challenge is compounded by adversarial environments in which blockchain networks operate, where validators cannot be assumed trustworthy and may attempt to corrupt systems by providing false information or refusing to participate. Inter-shard consensus protocols must be robust against such attacks while minimizing latency and communication overhead that cross-shard coordination introduces.

Inter-shard communication protocols define how shards exchange information about cross-shard transactions and coordinate state transitions. These protocols typically operate in phases where shards first validate their portions of cross-shard transactions locally, then communicate with other involved shards to determine whether all prerequisites are satisfied, and finally apply state changes or abort transactions based on coordinated decisions. Specific message flows and voting mechanisms vary across blockchain platforms, but they generally follow patterns similar to atomic commitment protocols from distributed systems literature, adapted to account for specific requirements and constraints of blockchain environments.

Validator rotation schemes address security concerns about shard-specific attacks by periodically reassigning validators to different shards. If the same validators were permanently assigned to particular shards, attackers could concentrate efforts on corrupting those specific validator sets. By randomly rotating validators between shards at regular intervals, systems ensure attackers would need to control significant fractions of entire validator populations rather than just targeting single shards. Rotation must be done carefully to avoid vulnerability windows during transition periods when validator sets are changing, and randomness used for assignment must be unbiasable to prevent attackers from manipulating assignment processes to their advantage.

Preventing double-spending across shards requires mechanisms ensuring the same asset cannot be spent multiple times through concurrent transactions on different shards. In traditional blockchains, double-spending is prevented by having all validators process transactions in single global order, so they can easily detect attempts to spend the same funds twice. With sharding, this becomes more complex because different shards may initially process transactions independently without awareness of concurrent transactions on other shards. Cross-shard transaction protocols must include checks preventing double-spending by ensuring that when assets are transferred between shards, they are provably removed from source shards before being created on destination shards, and that this operation happens atomically to prevent scenarios where assets are lost or duplicated.

Real-World Implementations and Case Studies

Examining actual implementations of cross-shard transaction processing in production blockchain systems provides invaluable insights into practical challenges and effectiveness of different approaches. Three major platforms represent distinct design points, each making different architectural choices reflecting their priorities and lessons learned from earlier systems. Ethereum’s evolution toward sharding through data availability sampling, Zilliqa’s pioneering implementation of network and transaction sharding, and Polkadot’s parachain architecture with cross-chain messaging demonstrate the diversity of viable approaches to achieving scalability through partitioning.

Ethereum’s approach to sharding has evolved significantly as the platform matured and the research community developed better understanding of trade-offs involved. The original roadmap envisioned full state sharding where the network would be divided into many shards, each maintaining its own portion of account state and executing transactions independently. However, recognizing the enormous complexity this would entail, particularly for cross-shard transactions involving smart contracts, the Ethereum development community pivoted toward a rollup-centric scaling strategy where layer-two rollup protocols handle most transaction execution while the layer-one chain provides data availability and settlement.

Proto-Danksharding, formally specified as EIP-4844 and implemented on Ethereum mainnet in March 2024 through the Cancun-Deneb upgrade, represents Ethereum’s first major step toward this vision. Rather than implementing full execution sharding immediately, Proto-Danksharding introduces blob-carrying transactions that allow rollups to post transaction data to Ethereum much more cheaply than using traditional calldata. These data blobs are stored temporarily and do not need processing by the Ethereum Virtual Machine, significantly reducing costs while providing data availability guarantees that rollup protocols require for security. The implementation brought six blobs per block initially, with each blob containing approximately 125 kilobytes of data.

The technical innovation of Proto-Danksharding centers on polynomial commitments using KZG cryptography, which allows efficient verification that committed data is available without requiring all validators to download and store all blob data permanently. Looking forward, full Danksharding aims to scale this approach to 64 blobs per block through distributed data sampling techniques, where validators only need to sample small random portions of blob data to verify availability with high probability. This scaling path avoids the most complex aspects of cross-shard transaction coordination by keeping execution unified at the rollup layer while sharding only the data availability layer.

Zilliqa represents one of the first blockchain platforms to implement sharding in production, launching its mainnet with network sharding in June 2019. The platform divides the network into multiple shards that process transactions in parallel, using a hybrid consensus mechanism employing proof-of-work for shard formation and Practical Byzantine Fault Tolerance for consensus within shards. Each shard processes transactions where both sender and recipient accounts belong to that shard, enabling parallel transaction processing that increases throughput roughly linearly with shard count. Zilliqa’s approach notably simplifies cross-shard complexity by routing transactions that span multiple shards through a special Directory Service committee acting as a coordination layer.

The Zilliqa 2.0 upgrade, which began rolling out in 2024, introduced significant architectural improvements including transition from proof-of-work to proof-of-stake consensus, introduction of x-shards that allow developers to create customized blockchain environments with configurable parameters, and improved cross-shard communication mechanisms. The x-shard architecture enables developers to launch sovereign shards tailored for specific applications with their own governance rules, block times, and privacy settings, while still benefiting from shared network security. This modular approach addresses key limitations of the original Zilliqa design by allowing applications with specific requirements to optimize their shard parameters.

Polkadot takes a distinctly different architectural approach through its parachain model, where independent blockchains called parachains connect to a central relay chain providing shared security and facilitating inter-chain communication. While not sharding in the traditional sense of partitioning a single state machine, Polkadot’s architecture achieves similar scalability benefits by allowing multiple chains to process transactions in parallel. Each parachain can be optimized for specific use cases with its own state transition function, consensus rules, and governance mechanisms, while the relay chain handles cross-chain message routing and provides security through a nominated proof-of-stake system with hundreds of validators.

Cross-Consensus Messaging protocol forms the foundation of inter-parachain communication in Polkadot, providing a standardized format for parachains to exchange arbitrary data and invoke operations across chain boundaries. Unlike cross-shard protocols maintaining consistency within a single unified state machine, XCM operates in heterogeneous environments where different parachains may have completely different state structures and execution environments. Rather than attempting to provide strong atomicity guarantees for arbitrary cross-chain operations, XCM embraces eventual consistency and allows parachains to define their own error handling and rollback mechanisms.

The platform achieved significant scaling milestones in 2024, with daily rollup extrinsics increasing 69 percent quarter-over-quarter to reach 763,000 daily transactions in the third quarter. Projects like Frequency, Litentry, and Mythos drove this growth by building applications leveraging Polkadot’s scalability while benefiting from shared security. The expansion to 400 active validators with plans to reach 500 represents substantial decentralization. Asynchronous backing, deployed in 2024, provides up to eightfold improvement in scalability by allowing parachain block producers to work on future blocks in advance and reducing wasted block space.

Benefits and Challenges

Adopting cross-shard transaction processing technology offers transformative benefits addressing fundamental limitations of traditional blockchain architectures, but these advantages come alongside significant challenges requiring careful management. Understanding both opportunities and obstacles is essential for anyone building or working with sharded blockchain platforms, as the balance between benefits and costs often determines whether sharding makes sense for particular applications.

Performance improvements represent the most obvious benefit of sharding and cross-shard transaction processing. By allowing multiple shards to process transactions in parallel, sharded blockchains can achieve throughput scaling roughly linearly with shard count. A network with ten shards can theoretically process ten times as many transactions per second as a single-chain network with equivalent validator resources per shard. Platforms implementing sharding have demonstrated throughput in thousands or tens of thousands of transactions per second, approaching or exceeding traditional centralized payment systems.

Reduced latency for many transactions accompanies these throughput improvements because transactions affecting only state within single shards can be processed by that shard’s validators without requiring coordination with other shards. Consensus latency and block production time for such transactions depends only on intra-shard consensus mechanisms rather than requiring global coordination. This enables applications built on specific shards or parachains to achieve confirmation times measured in seconds.

Better resource utilization emerges from distributing computational, storage, and bandwidth requirements across many nodes rather than requiring every node to process every transaction. Validators can specialize in validating particular shards, allowing efficient operation on more modest hardware than required to validate entire high-throughput blockchains. This democratization of validation reduces barriers to entry for running validator nodes and supports greater decentralization.

Horizontal scalability provides a path for blockchain networks to grow with increasing demand by adding more shards as transaction volumes increase. Unlike vertical scaling approaches requiring ever-more-powerful hardware for individual nodes, horizontal scaling through sharding distributes load across more nodes operating in parallel. This approach aligns well with decentralized philosophy because it allows networks to scale without concentrating power or creating stronger dependencies on specialized infrastructure providers.

Advantages of Cross-Shard Processing

Improved developer experience emerges as applications can be built with confidence that underlying blockchain infrastructure can scale to meet their needs without requiring fundamental architectural changes. Developers can design applications knowing that if user bases grow substantially, blockchain platforms can accommodate increased transaction volumes through additional shards or improved cross-shard communication protocols.

Economic efficiency improvements arise from reduced transaction fees as increased capacity alleviates congestion driving up prices during high demand periods. When blockchain networks approach throughput limits, users must compete by offering higher transaction fees to incentivize validators to include their transactions in blocks. This creates situations where transaction fees can spike to levels making small-value transactions uneconomical. Sharding’s increased capacity reduces congestion and allows transaction fees to remain at lower, more predictable levels supporting broader use cases.

Enhanced network effects become possible as sharded blockchains can support larger and more diverse ecosystems of applications and users without succumbing to congestion and degraded performance. Each application or user community can potentially operate primarily within specific shards while still being able to interact with users and applications on other shards when needed. This creates network effects similar to the internet where many networks are interconnected through routing protocols.

Greater resilience to attacks can result from the distributed nature of sharded systems where compromising single shards does not necessarily compromise entire networks. Security mechanisms like random validator assignment and rotation, cross-shard verification, and fraud proofs can detect and contain breaches within individual shards before they affect broader systems. The independence of shards also means certain types of attacks that would congest or disable entire single-chain networks might only affect subsets of shards in sharded systems.

Technical Limitations and Barriers

Increased complexity represents perhaps the most significant challenge facing sharded blockchain systems. Cross-shard transaction protocols are substantially more complex than single-shard transactions, requiring sophisticated coordination mechanisms, careful handling of failure scenarios, and extensive testing to ensure correctness. This complexity affects not only core protocol implementation but also developer tools, user interfaces, and operational monitoring systems that must understand and properly handle cross-shard operation nuances.

Communication overhead between shards can consume much of the performance benefit that sharding provides if cross-shard transactions are frequent. Each cross-shard transaction requires multiple communication rounds between involved shards, potentially introducing latency measured in seconds or even minutes depending on specific protocol and network conditions. If application transaction patterns require frequent cross-shard communication, systems may perform no better or even worse than unsharded architectures.

Security concerns arise from reduced validator sets assigned to individual shards compared to full validator sets securing unsharded chains. Attackers need to corrupt fewer validators to compromise single shards than would be required to compromise entire unsharded networks. While techniques like random validator assignment mitigate this concern, the fundamental trade-off remains between individual shard security and partitioning scalability benefits.

Difficulty in achieving true atomicity across shards becomes apparent when examining actual protocols implemented by sharded blockchains. Many systems provide weaker consistency guarantees than traditional ACID properties, accepting eventual consistency or requiring applications to implement their own compensation mechanisms for handling partial failures. While these relaxed guarantees may be acceptable for some applications, others require strong atomicity that may be difficult or impossible to achieve efficiently in highly sharded systems.

User experience challenges emerge when cross-shard operations have substantially different latency or cost characteristics than single-shard operations. Users may not understand why some transactions confirm quickly while others take much longer, or why transaction fees vary dramatically depending on which shards are involved. Wallet and application interfaces must clearly communicate these differences while ideally abstracting away complexity that users should not need to understand.

Final Thoughts

Cross-shard transaction processing stands as one of the most significant technical achievements in blockchain evolution, representing a critical bridge between the vision of globally scalable decentralized systems and the practical reality of building networks serving billions of users. The journey from simple single-chain architectures to sophisticated sharded systems capable of processing thousands or millions of transactions per second demonstrates both the remarkable ingenuity of blockchain researchers and developers and the complexity inherent in distributed consensus systems operating in adversarial environments.

The transformative potential of this technology extends beyond simply making existing blockchain applications faster or cheaper. By fundamentally changing scalability characteristics of decentralized systems, cross-shard transaction processing enables entirely new categories of applications impossible or impractical on traditional blockchains. Financial applications requiring high-frequency trading, gaming platforms with millions of active users, social networks generating constant streams of microtransactions, supply chain systems tracking billions of items, and identity systems serving global populations all become feasible when blockchain networks can scale horizontally through effective sharding implementations.

The broader implications for financial systems and economic inclusion deserve particular attention. Traditional financial infrastructure has created enormous value but remains inaccessible to billions worldwide due to geographic, economic, and political barriers. Blockchain technology promises more inclusive financial systems that anyone with internet access can participate in, but only if underlying networks can scale to serve global populations. Cross-shard transaction processing provides the technical foundation for blockchain systems to achieve necessary throughput for global financial inclusion while maintaining decentralization and censorship resistance properties that make blockchain technology valuable.

The intersection of technology and social responsibility becomes especially important when considering how sharding and cross-shard transactions affect blockchain network accessibility and fairness. Well-designed sharded systems can reduce transaction costs and improve accessibility by eliminating congestion and allowing more participants to contribute to network security through validation. Poorly designed systems might inadvertently create new barriers or concentrate power among entities capable of operating infrastructure across multiple shards. Technical choices made in designing cross-shard transaction protocols have real consequences for who can participate in these networks and how equitably they operate.

Looking toward the future, successful maturation of cross-shard transaction processing will likely catalyze new waves of blockchain innovation as developers gain confidence that scalability will not limit their applications. The convergence of multiple scaling techniques including sharding, layer-two rollups, and cross-chain communication protocols creates rich ecosystems where different approaches can be combined to achieve optimal performance for specific use cases. Applications will increasingly span multiple chains and shards, relying on sophisticated cross-domain coordination protocols to provide seamless user experiences.

The ongoing challenges should not be dismissed as temporary technical obstacles that will automatically resolve as technology advances. Security properties in sharded systems require constant vigilance and continued research to identify and address new attack vectors. User experience improvements demand sustained attention to interface design and education rather than expecting users to understand complex technical details. Economic sustainability of sharded networks depends on finding right incentive structures that properly reward validators, developers, and other participants while keeping transaction costs reasonable for end users.

Innovation and accessibility must remain balanced as cross-shard transaction technology matures and gains broader adoption. The most sophisticated technical solution provides limited value if it cannot be understood and used by developers and users who need it. Abstractions hiding complexity while preserving essential security properties will be crucial for enabling mainstream adoption.

FAQs

- What exactly is a cross-shard transaction and how does it differ from a regular transaction?

A cross-shard transaction is a transaction that reads or writes data stored on multiple shards in a sharded blockchain network, requiring coordination between the involved shards to maintain consistency. Regular transactions that affect only state within a single shard can be processed entirely by that shard’s validators using local consensus. Cross-shard transactions are more complex because they need coordination protocols to ensure that operations affecting multiple shards either complete entirely across all involved shards or have no effect on any shard, maintaining properties like atomicity and preventing issues such as double-spending of assets across shard boundaries. - Why can’t sharded blockchains just process each shard’s transactions independently without cross-shard coordination?

Complete independence between shards would make it impossible for assets or information to move between shards, severely limiting the system’s functionality. Users need to be able to transfer value between accounts on different shards, smart contracts need to access data from multiple shards, and the system must maintain global invariants like conservation of total supply. Without cross-shard coordination protocols, a user could potentially spend the same funds multiple times on different shards, or a transfer between shards could result in funds disappearing from one shard without appearing on another. Coordination ensures these operations happen safely and consistently. - How much slower are cross-shard transactions compared to single-shard transactions?

Cross-shard transactions typically take longer to process than single-shard transactions because they require additional communication rounds between shards and more complex validation procedures. The exact performance difference depends on the specific blockchain platform, network conditions, and coordination protocol used. Cross-shard transactions might take anywhere from two to ten times longer than comparable single-shard transactions, though optimization techniques can reduce this overhead. For users, this might mean confirmation times of several seconds to a minute or more for cross-shard operations compared to single-digit seconds for intra-shard transactions. - Can developers optimize their applications to minimize cross-shard transactions?

Yes, careful application design can substantially reduce the frequency and impact of cross-shard transactions. Developers can partition data and logic to keep related accounts, contracts, and state on the same shard when possible. Using techniques like batching multiple operations together, designing workflows that minimize state dependencies across shards, and implementing caching strategies can reduce cross-shard communication overhead. Some platforms provide tools to analyze transaction patterns and suggest optimizations. However, some applications inherently require frequent cross-shard interactions, and optimization can only reduce rather than eliminate this overhead. - What happens if a cross-shard transaction fails partway through execution?

Atomic commitment protocols ensure that cross-shard transactions either complete fully or have no effect on any involved shard. If any shard cannot complete its portion of the transaction due to validation failure, insufficient resources, or other issues, the entire transaction aborts and all shards roll back any tentative state changes. Users who initiated failed cross-shard transactions may need to pay gas fees for the computational work performed, even though the transaction did not complete, though some platforms refund fees for certain types of failures. Applications should implement appropriate error handling and retry logic for cross-shard operations. - Are cross-shard transactions more expensive than regular transactions?

Cross-shard transactions generally cost more than single-shard transactions because they require additional computational and communication resources for coordination between shards. Users typically pay higher gas fees for cross-shard operations to compensate validators for this extra work. The exact cost difference varies by platform and specific transaction complexity, but cross-shard operations might cost anywhere from fifty percent to several times more than comparable single-shard transactions. However, on sharded blockchains, even cross-shard transactions may be cheaper than transactions on congested unsharded networks due to reduced overall network congestion. - How do sharded blockchains prevent an attacker from corrupting just one shard?

Multiple security mechanisms protect against shard-specific attacks. Random assignment of validators to shards prevents attackers from targeting specific shards. Periodic rotation of validators between shards means an attacker would need to maintain control over different validator sets over time. The broader network monitors individual shards for misbehavior through fraud proofs and verification mechanisms that allow detecting invalid state transitions. Some platforms require shards to post cryptographic proofs of correct execution that can be verified by the broader network. Economic penalties and slashing mechanisms discourage validators from participating in attacks by making successful attacks expensive relative to potential gains. - Will all blockchain networks eventually use sharding and cross-shard transactions?

Not necessarily, as different blockchain platforms make different trade-offs based on their priorities and use cases. Some networks prioritize simplicity and security over maximum throughput and may continue using single-chain architectures supplemented by layer-two scaling solutions. Others focus on specific applications that can be optimized differently. Sharding makes most sense for platforms aiming to support diverse applications with high transaction volumes while maintaining decentralization. The blockchain ecosystem likely will include a mix of sharded and unsharded networks, each optimized for different requirements. - How can users tell if their transaction will require cross-shard coordination?

Most blockchain platforms abstract sharding details from users, automatically routing transactions appropriately without requiring users to understand shard assignments. However, some platforms provide interfaces showing which shard accounts or contracts belong to, allowing users to predict when operations will cross shard boundaries. Advanced users and developers can use blockchain explorers and analytics tools to examine shard topology and optimize their transaction patterns. The goal for most platforms is making cross-shard transactions as transparent as possible so users receive consistent experiences regardless of whether shards are involved. - What are the main research challenges that still need to be solved for cross-shard transactions?

Several important research areas remain active. Improving the efficiency of cross-shard atomic commitment protocols to reduce latency and communication overhead continues to be important. Developing better techniques for preventing and detecting attacks on sharded systems requires ongoing work. Creating abstractions and developer tools that make it easier to build applications on sharded platforms without deep protocol knowledge remains challenging. Research into optimal shard assignment strategies, dynamic shard reconfiguration based on workload patterns, and techniques for minimizing the frequency of cross-shard operations could substantially improve practical performance of sharded blockchains.